By John M. Hotchner

What do you see when you receive a stamp on an envelope or at a post office? The average user of the mails might notice a bit of color; maybe even the subject or design, but by 20 minutes later most could not tell you what the design illustrated.

Stamp collectors are different. We look at the stamp, classify it according to whether it is a comm on variety or something more interesting, and decide whether to keep it. And perhaps at the subconscious level, we also evaluate modern stamps in the context of what has gone before — and for many of us, the comparison is often not positive.

on variety or something more interesting, and decide whether to keep it. And perhaps at the subconscious level, we also evaluate modern stamps in the context of what has gone before — and for many of us, the comparison is often not positive.

For most people, stamps are a means to an end. For collectors, they can be that, but most importantly, they are an end in themselves. So, what is it that collectors find attractive and unattractive about these objects of our affection? At the most obvious level, which the non-collector also sees but may not appreciate, there are ten factors:

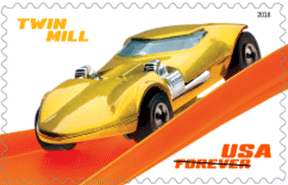

a. Color, either monocolor or multicolor. Most of today’s stamps are a mix of colors because the general public has voted for this with their wallets. They find multicolor more pleasing and attractive, regardless of what the colors may be. Collectors tend to notice the colors used, and make judgments about the attractiveness, the appropriateness, and the arrangement of the colors.

b. Print Quality, Part I For collectors, especially those of the old school, the Gold Standard is single color that has been printed by recess engraving. We find these examples of the engraver’s and printer’s art near irresistible. Unfortunately, th ey are more expensive to produce and have become a victim of the Postal Service’s bean counters. The USPS budgeting process values cost avoidance before all else; second, revenue, and then in third place they may evaluate how customer preference might intersect with the other two. They see collectors more as cash cows to be milked than as a constituency to be pleased (though I don’t think the Citizens’ Stamp Advisory Committee totally buys into that), so we don’t see many recess engraved stamps among the new issues of the United States. Of the majority, whether we can identify them or not, we tend to react better to photogravure printing than offset.

ey are more expensive to produce and have become a victim of the Postal Service’s bean counters. The USPS budgeting process values cost avoidance before all else; second, revenue, and then in third place they may evaluate how customer preference might intersect with the other two. They see collectors more as cash cows to be milked than as a constituency to be pleased (though I don’t think the Citizens’ Stamp Advisory Committee totally buys into that), so we don’t see many recess engraved stamps among the new issues of the United States. Of the majority, whether we can identify them or not, we tend to react better to photogravure printing than offset.

c. Print Quality, Part II Advances in printing technology have over the years since our first postage stamps in 1847, improved the uniformity and the quality of stamps coming off the presses. It used to be that a collector could make their life’s work the study of a single stamp in all its varieties. On most of today’s stamps, it is a struggle to find an example that differs in any significant way from all its brothers and sisters.

d. The Topic/Subject may be the first thing we all consciously notice and react to. For the general public, it may be the only criterion for what to buy, while collectors have more subtle and more complicated re actions. All buyers/viewers like a pretty flower stamp. But for the general public, that is where it ends. For collectors, a little of that (puppies, lighthouses, birds, costumes, etc.) goes a long way. We prefer topics with some gravitas: history illustrated though events and the people who excelled in their fields and contributed to making America great, events that advance the human condition like space stamps, scientific discoveries and medical advances.

actions. All buyers/viewers like a pretty flower stamp. But for the general public, that is where it ends. For collectors, a little of that (puppies, lighthouses, birds, costumes, etc.) goes a long way. We prefer topics with some gravitas: history illustrated though events and the people who excelled in their fields and contributed to making America great, events that advance the human condition like space stamps, scientific discoveries and medical advances.

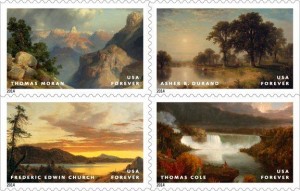

e. The Design is of little importance to the general public, but of supreme importance to collectors. The Postal Service has two responsibilities here: First, to convey the subject clearly on a small palette, and second, to reflect the full range of American art styles in its stamps. That includes, among others, abstract art, comic art, impressionism, pop art and photography. But a large percentage of collectors are traditionalists; not fond of anything not, well, traditional. So, collectors have a full range of thoughts and feelings on the art used for any given subject. While cocktail parties talk Trump, stamp club meetings talk stamp design trends, especially as represented on new issues.

f. The Size which is always “the bigger the better” unless you are the public, having to carry around giant Priority Mail, Express Mail or large commemorative stamps. Now, the reality is that the extra weight and size of large commemoratives is hardly worth considering, but the general public has its concerns and this is undeniably one of them. Collectors on the other hand generally revel in ‘bigger is better’ when contemplating stamps they liked, but will immediately jump to critic mode when the stamp is a large version of something they don’t like.

g. Stamp Shape which draws the same kinds of complaints when non-traditional circular, especially tall or wide, or triangular stamps are issued. The USPS sees these as interesting variations on what might otherwise be a boring theme, and believes they bait the stamp collecting hook (of which more later), but collector reaction is by and large not complimentary.

g. Stamp Shape which draws the same kinds of complaints when non-traditional circular, especially tall or wide, or triangular stamps are issued. The USPS sees these as interesting variations on what might otherwise be a boring theme, and believes they bait the stamp collecting hook (of which more later), but collector reaction is by and large not complimentary.

h. Stamps In Souvenir Sheets clearly intended by the USPS not for postal use but for collectors. Few such sheets are used on mail, but then, it requires real effort to remove the postage from the excess paper for use. So, while many collectors enjoy them as philatelic souvenirs, the same collectors may be annoyed, feeling that they are being fleeced.

i. Face Value has risen with inflation, and has risen even faster if Priority Mail, Express Mail and souvenir sheets are counted in. The public buys what they need and it is fee for service. But it requires a real act of will for a collector to lay out over $80 for a new Express Mail plate block (every 18 months or so), and in this way, the USPS is pricing itself out of the market as the vast majority of stamp collectors are not in that league.

j. Multi-Stamp Sets combined with face value, make even relatively inexpensive stamps an investment when there are 10 or 20 different pets, Harry Potter characters,  Peanuts Christmas stamps, etc. It used to be this was limited to commemorative subjects, but in recent years the Postal Service has extended it into the domain of definitives. All of this tends to encourage stamp collectors to avoid mint stamps, and to concentrate on used. (But even this is more difficult to swing now that most self-sticks can’t be washed.)

Peanuts Christmas stamps, etc. It used to be this was limited to commemorative subjects, but in recent years the Postal Service has extended it into the domain of definitives. All of this tends to encourage stamp collectors to avoid mint stamps, and to concentrate on used. (But even this is more difficult to swing now that most self-sticks can’t be washed.)

At the second level are the technical details of the stamp. These are almost totally ignored by the general public if they are noticed at all. Again there are multiple aspects:

a. The Paper Used, And Its Color which can be bright to dull, thin to thick, coated or not, and pregummed or gummed after printing. In the olden says, there was also the issue of watermarks.

b. The Tagging which can be in the paper, on top of the paper, overall or block, and can fluoresce in many colors.

c. The Gum which can be flat or shiny, ridged or not, and self-stick (with the consequent problems of aging and nonwashability). On this one there is a sharp split between collectors and non-collectors. The latter generally love self-sticks. Collectors are ok with them if used stamps can be washed from envelops, but unalterably opposed, with flashes of anger, if they don’t wash.

d. The Means Of Separation which used to be simple perforations (holes between the stamps), but has now moved on to die cuts of various shapes and sizes often with several variations on the stamps of a single issue.

e. Added Factors such as plate numbers and what they represent, the copyright or issue date, secret marks to deter counterfeiting (often in the form of microprinting, or opticalvariable devices), and backing paper which is now an integral part of collecting a “mint” stamp.

Collectors may ignore or study the multiple variations in each of these second level categories.

At the third level; some of which are obvious even to the non-collector, and many of which are not, are unintended production varieties. These are often termed in philately EFOs, for  Errors, Freaks and Oddities. Each of these is a term of art that has a lengthy definition, and if you want to learn more about this area, visit www.efocc.org, the website of the EFO Collectors Club.

Errors, Freaks and Oddities. Each of these is a term of art that has a lengthy definition, and if you want to learn more about this area, visit www.efocc.org, the website of the EFO Collectors Club.

To the extent that the general public cares about these at all, it is because they have found something really obvious like a missing color, or unintended imperfs. Sometimes they will turn these back into the post office, saying something like, “Take these back and give me good ones that I can use.” For the more philatelically aware, the immediate question is how do they turn these into money?

Collectors are more likely to keep EFOs, as even minor examples are relative rarities. The truly dedicated will also use EFOs as a window on the production process; as a means of understanding the fascinating world of stamp printing.

Can we learn anything from this brief review of the properties of a stamp, and the differences in how stamps are seen by collectors and non-collectors?

I think a primary lesson is that the USPS is in a no-win situation. In order to get the attention of non-collectors and to draw them into the hobby, they have to produce an unending stream of stamps with popular themes that the general public will pay attention to, but which dyed-in-the-wool collectors often find annoying and manipulative.

Another is that there is much more to stamps than the general public ever thinks about, and much more for collectors to think about and enjoy than most have time, money or inclination for.

The “old” way of collecting a mint example of every stamp the United States has issued is now a huge challenge (with over 5500 different stamps; many of the earliest examples beyond the ability of our wallets to acquire). So country collecting — even in used-stamps form — is giving way to topical collecting and discreet time period-collecting.

Very little of this is obvious to us as we look at a stamp we buy or receive on an envelope today.

Should you wish to comment on this editorial, or have questions or ideas you would like to have explored in a future column, please write to John Hotchner, VSC Contributor, P.O. Box 1125, Falls Church, VA 22041-0125, or email, putting “VSC” in the subject line.

Or comment right here.

So, in this day of $200 sneakers, $75 jeans being sold new with ripped knees, must-have electronics, and designer tops for kids that adults can’t afford, is it any wonder that money is high on the radar screens of kids who are probably not told enough, “No, we can’t afford that!”

So, in this day of $200 sneakers, $75 jeans being sold new with ripped knees, must-have electronics, and designer tops for kids that adults can’t afford, is it any wonder that money is high on the radar screens of kids who are probably not told enough, “No, we can’t afford that!” interested in how high they could score playing Pac-Man and the immediate feedback that offered, than in spending time on the laborious process of building a stamp collection; which offered no element of competition among their peers, and little in the way of immediate feedback.

interested in how high they could score playing Pac-Man and the immediate feedback that offered, than in spending time on the laborious process of building a stamp collection; which offered no element of competition among their peers, and little in the way of immediate feedback. We did it as kids because we had time on our hands, with few other distractions, and we enjoyed the act of organizing our collection, and the pride of learning about other nations, and American history from stamps.

We did it as kids because we had time on our hands, with few other distractions, and we enjoyed the act of organizing our collection, and the pride of learning about other nations, and American history from stamps. tices in out-of-the-way literature.

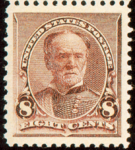

tices in out-of-the-way literature. Poking through the U.S. cover stock of a dealer from another country, I saw a cut square with the dollar values of the 1938 Prexie series, priced at $35. Cancelled in New York City on February 8 of a year that is unclear, it is shown in Figure 1. Given that the catalogue values of the three used stamps is $7, I hesitated. The combination is unusual, but 5x catalog unusual?

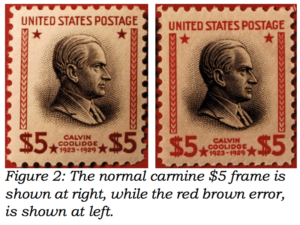

Poking through the U.S. cover stock of a dealer from another country, I saw a cut square with the dollar values of the 1938 Prexie series, priced at $35. Cancelled in New York City on February 8 of a year that is unclear, it is shown in Figure 1. Given that the catalogue values of the three used stamps is $7, I hesitated. The combination is unusual, but 5x catalog unusual? But wait — something about that $5 rang a bell. The reddish frame color was much darker than the normal “carmine” noted in the Scott Catalogue. Having seen this before on mint $5 examples submitted for expertizing, my mind’s eye pictured a reference photo I had been given by the late Joseph Thompson, who was a scholar in this realm. The photo is shown in Figure 2.

But wait — something about that $5 rang a bell. The reddish frame color was much darker than the normal “carmine” noted in the Scott Catalogue. Having seen this before on mint $5 examples submitted for expertizing, my mind’s eye pictured a reference photo I had been given by the late Joseph Thompson, who was a scholar in this realm. The photo is shown in Figure 2. My conclusion is that there is every likelihood that the Figure 1 example is genuine. I will submit it for expertizing, and report the results here once I have received the opinion.

My conclusion is that there is every likelihood that the Figure 1 example is genuine. I will submit it for expertizing, and report the results here once I have received the opinion. “For mint singles, blocks, etc., I do likewise, except that I use the pitch-outs for postage. Mostly with stuff like that I run into thins or disturbed gum as a disqualifier. As to centering, if it is only Fine — it goes into my scrap postage box.

“For mint singles, blocks, etc., I do likewise, except that I use the pitch-outs for postage. Mostly with stuff like that I run into thins or disturbed gum as a disqualifier. As to centering, if it is only Fine — it goes into my scrap postage box. “Bottom line is when I returned home I ordered, from the national firm, a Scott #560 (8¢ Perf. 11×11, 1922) plate block, Mint, Never Hinged, in Very Fine to Extra Fine condition. I got an immediate reply saying that they have been unable to keep this in inventory for the past ten years. Just in case the reply was wrong, I tried again this past February. Same result, except that as a courtesy, they noted that had recently acquired some plate blocks of the 1922 issue, but they were only in Fine condition, and would I be interested? I would not.

“Bottom line is when I returned home I ordered, from the national firm, a Scott #560 (8¢ Perf. 11×11, 1922) plate block, Mint, Never Hinged, in Very Fine to Extra Fine condition. I got an immediate reply saying that they have been unable to keep this in inventory for the past ten years. Just in case the reply was wrong, I tried again this past February. Same result, except that as a courtesy, they noted that had recently acquired some plate blocks of the 1922 issue, but they were only in Fine condition, and would I be interested? I would not. “Thus, I have decided to continue my efforts of accumulating, and at my demise, deed over to my son all of my philatelic holdings. What I’ve set aside for him will be used to augment his business as a dealer when he retires. For now he is a collector of mint singles, but then he will also have a large holding of high-grade plate blocks. By doing this, we will just bypass all the con artists.

“Thus, I have decided to continue my efforts of accumulating, and at my demise, deed over to my son all of my philatelic holdings. What I’ve set aside for him will be used to augment his business as a dealer when he retires. For now he is a collector of mint singles, but then he will also have a large holding of high-grade plate blocks. By doing this, we will just bypass all the con artists. What this means is that most of us who are 50 and above long for the good old days of engraved stamps; which we think of as more intricately designed, and with ink raised off the paper that gives both a feel and a visual impression of quality. Indeed, a well-designed stamp produced by intaglio is a thing of beauty.

What this means is that most of us who are 50 and above long for the good old days of engraved stamps; which we think of as more intricately designed, and with ink raised off the paper that gives both a feel and a visual impression of quality. Indeed, a well-designed stamp produced by intaglio is a thing of beauty. Perhaps the closest model we have within the hobby today is the people who collect Christmas subjects on stamps, especially those who collect traditional religious images which are overwhelmingly classic artworks.

Perhaps the closest model we have within the hobby today is the people who collect Christmas subjects on stamps, especially those who collect traditional religious images which are overwhelmingly classic artworks. the artists themselves, and many other categories. And yes, even art produced specifically as models for stamp designs and the stamp designs themselves.

the artists themselves, and many other categories. And yes, even art produced specifically as models for stamp designs and the stamp designs themselves. 2. Let’s have much more publicity by the USPS about the design process, the rejected designs, and why the design chosen was selected. As part of this effort (which stamp collectors also find fascinating), have the CSAC Design Coordinators make “YouTube” videos on their craft to circulate to art appreciation groups, and have them address conventions of appropriate groups.

2. Let’s have much more publicity by the USPS about the design process, the rejected designs, and why the design chosen was selected. As part of this effort (which stamp collectors also find fascinating), have the CSAC Design Coordinators make “YouTube” videos on their craft to circulate to art appreciation groups, and have them address conventions of appropriate groups. 4. Hobby institutions (USPS/APS/Specialty societies focused on a design theme that includes art) can partner with art museums to present the art of philately in featured exhibits.

4. Hobby institutions (USPS/APS/Specialty societies focused on a design theme that includes art) can partner with art museums to present the art of philately in featured exhibits. 6. We can work with school art appreciation programs/teachers to include the miniature art of stamps in the curriculum, and use stamp design contests to teach elements of composition. There could even be doctoral dissertations looking into the progression of artistic style in U.S. stamps, and other art/stamps subjects.

6. We can work with school art appreciation programs/teachers to include the miniature art of stamps in the curriculum, and use stamp design contests to teach elements of composition. There could even be doctoral dissertations looking into the progression of artistic style in U.S. stamps, and other art/stamps subjects. but often enough to support and encourage those whose collecting motivation is in this sector.

but often enough to support and encourage those whose collecting motivation is in this sector. But are the changes really fatal, or do they simply force changes in collecting with which we are unhappy? Are we over-reacting to what we see as high handedness on the part of the USPS? Personally, I feel it, and there can be little doubt that there is some of this in the reaction of collectors. As confirmation, we saw it in letters to the editor in the philatelic press as the USPS went to unwashable self-sticks, and then decreed that all issues would be self-sticks.

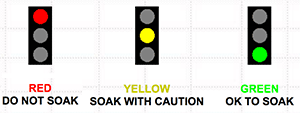

But are the changes really fatal, or do they simply force changes in collecting with which we are unhappy? Are we over-reacting to what we see as high handedness on the part of the USPS? Personally, I feel it, and there can be little doubt that there is some of this in the reaction of collectors. As confirmation, we saw it in letters to the editor in the philatelic press as the USPS went to unwashable self-sticks, and then decreed that all issues would be self-sticks. were soakable, through the hard work of volunteer John Cropper. Then he had to move on, and no one else was able to undertake this task. But the “Soaking Stoplight” information is still online here for

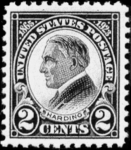

were soakable, through the hard work of volunteer John Cropper. Then he had to move on, and no one else was able to undertake this task. But the “Soaking Stoplight” information is still online here for  1. Find a U.S. Scott #613, the rotary press-printed 2¢ Black Harding, perf 11. There are about 65 examples known, and I believe there are more waiting to be discovered. Since buying one is out of the question (Cat. Value: $40,000), I measure every 2¢ Harding I come across. Maybe lightening will strike!

1. Find a U.S. Scott #613, the rotary press-printed 2¢ Black Harding, perf 11. There are about 65 examples known, and I believe there are more waiting to be discovered. Since buying one is out of the question (Cat. Value: $40,000), I measure every 2¢ Harding I come across. Maybe lightening will strike! 3. Solve the mystery of the 3¢ Servicewomen commemorative of 1952, Scott #1013, which features four servicewomen as portrayed by professional models. I know the name of one. Who are the others? Research in the les of the USPS, Bureau of Engraving and Printing, and Defense Department have failed to bring the names to light. Someone must know.?

3. Solve the mystery of the 3¢ Servicewomen commemorative of 1952, Scott #1013, which features four servicewomen as portrayed by professional models. I know the name of one. Who are the others? Research in the les of the USPS, Bureau of Engraving and Printing, and Defense Department have failed to bring the names to light. Someone must know.? project that needs some serious work.

project that needs some serious work. ne activities of Americans in the late 19th and early 20th centuries; from birth to death.

ne activities of Americans in the late 19th and early 20th centuries; from birth to death.