By John M. Hotchner

I received a letter that threw me for a bit of a loop. I’m going to quote it below, edited a bit to eliminate repetition, and then make a few comments. Yours would be welcome, too.

“I’m not a dealer per se. I am for all practical purposes an accumulator. I buy what I can, U.S. issues only. My holdings gathered over the last 65 years are extensive. I have no need or desire or intention to sell anything. What I’m doing in increasing my holdings is easy-going and enjoyable.

“I’m not a dealer per se. I am for all practical purposes an accumulator. I buy what I can, U.S. issues only. My holdings gathered over the last 65 years are extensive. I have no need or desire or intention to sell anything. What I’m doing in increasing my holdings is easy-going and enjoyable.

“When I make a purchase, I weed out everything used that is not of collector grade: anything torn, creased, stained, or with short perfs I simply discard. I do so because no one will buy things in those categories. Thus, out it goes.

“For mint singles, blocks, etc., I do likewise except that I use the pitch-outs for postage. Mostly with stuff like that I run into thins or disturbed gum as a disqualifier. As to centering, if it is only Fine – it goes into my scrap postage box.

“What upsets me most up here in the Midwest is that when one talks with a dealer about having them make an offer – they automatically tell you, ‘I’ve got all of that; not interested in buying any more, etc., etc.’ One cannot help but wonder how dealers stay in business without upgrading or expanding their own inventory.

“I bring this to your attention because of my experience at the American Philatelic Society stamp show in Milwaukee a few years ago. I approached the booth of a  major national stamp retailer who does a lot of advertising, and talked to the owner. I asked him if he would be interested in buying my duplicates from the 1922 definitive issue.

major national stamp retailer who does a lot of advertising, and talked to the owner. I asked him if he would be interested in buying my duplicates from the 1922 definitive issue.

“He told me, flat out, ‘No’…. Claimed they have all this stuff and would not be buying any more of it for the foreseeable future. Suggested I go and chat with another dealer present. I did and I purchased over $1000 worth of items for my personal holdings.

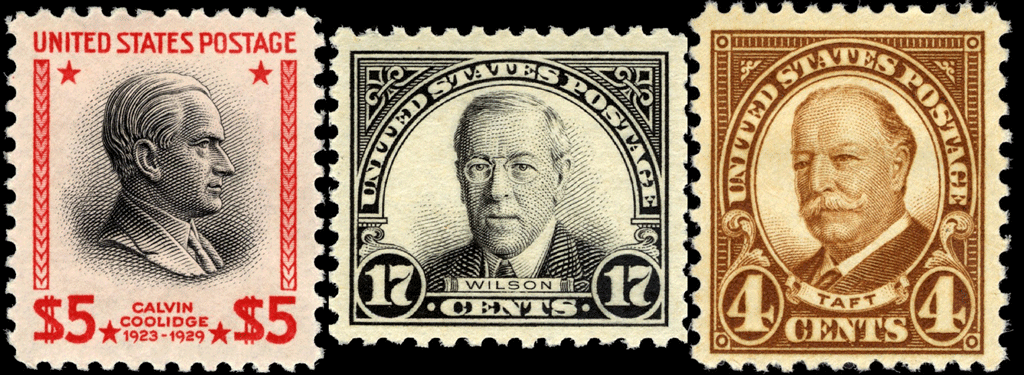

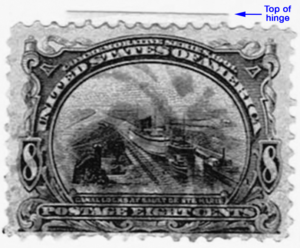

“Bottom line is when I returned home I ordered, from the national firm, a Scott #560 (8¢ Perf. 11×11, 1922) plate block, Mint, Never Hinged, in Very Fine to Extra Fine  condition. [editor’s note: The plate block shown is just for illustration purposes.] I got an immediate reply saying that they have been unable to keep this in inventory for the past ten years. Just in case the reply was wrong, I tried again this past February. Same result, except that as a courtesy, they noted they had recently acquired some plate blocks of the 1922 issue, but they were only in Fine condition, and would I be interested? I would not.

condition. [editor’s note: The plate block shown is just for illustration purposes.] I got an immediate reply saying that they have been unable to keep this in inventory for the past ten years. Just in case the reply was wrong, I tried again this past February. Same result, except that as a courtesy, they noted they had recently acquired some plate blocks of the 1922 issue, but they were only in Fine condition, and would I be interested? I would not.

“The point I make is this: Dealers and stamp company owners are for the most part totally unaware of what is actually happening with their own inventory; thus trying to deal with these people is a real – in your face – put down.

“However, if one works with their own holdings, we have a lot better idea of areas of weakness, and heavy duplication. Ignorance is expensive.

“Over the years I’ve read many offers to buy. One buyer from the Chicago area even  sent a representative up for a look-see about 10 years ago. He was definitely interested, but not in paying a fair price. He wanted to steal my holdings at 9% of catalogue value. He had the grace to look insulted when I rejected his offer.

sent a representative up for a look-see about 10 years ago. He was definitely interested, but not in paying a fair price. He wanted to steal my holdings at 9% of catalogue value. He had the grace to look insulted when I rejected his offer.

“Thus, I have decided to continue my efforts of accumulating, and at my demise, deed over to my son all of my philatelic holdings. What I’ve set aside for him will be used to augment his business as a dealer when he retires. For now, he is a collector of mint singles, but then he will also have a large holding of high-grade plate blocks. By doing this, we will just bypass all the con artists.

“I don’t know for certain if I am doing right by pushing the dealer issue down the road one generation – but it sure feels right to me and to my son. I have found that the hobby is a great way to stay in touch as a family.”

My comments (addressed to readers, not the letter writer as we have had subsequent correspondence): While disclaiming any intention of selling anything, our letter writer has made movements in that direction, and did not like the responses he got, so walked away from the deal. In another effort in that direction, he was rebuffed by a dealership where one hand seems not to know what the other hand is doing, and that experience ticked him off. I can sympathize. My reading is that he came to the no-sell decision after the experiences he describes.

While he indicates that he has 1922 material to sell, that is the earliest he mentions, and two things occur to me. First, while there is some good material in that era, stamps and even plate blocks in premium condition starting in the late 1920s are not difficult to find; and not difficult for dealers to purchase in bulk at favorable prices. Secondly, it is possible that the dealer(s) assumed that the bulk of the material offered was from the later era and truly did not fit in with their needs.

It is also possible that the dealer was put off by the manner of approach or another factor,  and chose not to do business with the letter-writer.

and chose not to do business with the letter-writer.

Stockpiling material from the era where good quality is available in quantity (say much of the material from the late 1920s to modern times) is not a good investment strategy. Yes, some items, carefully selected from among the most often seen material, can be good for investment: unfolded booklet panes, some popular theme se-tenants like Space and Lighthouses; high-face plate blocks, etc. are ok.

But the bottom dropped out of the plate block market many years ago in the 13¢ First Class era when the USPS tried to take advantage of the market by issuing 12-stamp plate blocks. It has never been restored to its former glory. Most from the 1940s-on sell wholesale in the  best circumstances at face, and even below. Consult catalogue prices to get an idea of what few plate blocks are more desirable.

best circumstances at face, and even below. Consult catalogue prices to get an idea of what few plate blocks are more desirable.

However, if one is determined to invest, the same amount of money put into classic material will bring better rewards. You will have less material, but it will appreciate. And it will sell more readily, and for better prices. Remember this rule of thumb: “Common material remains common. Proven high quality/limited quantity material appreciates.”

On dealers’ buy offers, two things: One is that they are entitled to try to pay the lowest price they can get away with. Don’t you as a collector try to pay the lowest possible price for your acquisitions? Second, while I am not claiming that 9% is a fair figure (though it is understandable for mostly modern stamps/blocks that will retail for half cat. or less.) keep in mind that dealers selling most modern material to knowledgeable collectors will not be able to get more than that, and may well get less; and they have their overhead to pay for. And, oh yes, the  object is to make a profit. For example, how much does it cost them to send a representative to visit and review your material in your home and make an offer?

object is to make a profit. For example, how much does it cost them to send a representative to visit and review your material in your home and make an offer?

That said, the seller always has the ultimate power: You can always try to negotiate a better price, and failing that, you can refuse to sell.

Finally, on the subject of kicking the can down to the next generation, it seems like a good strategy in this case as the son intends to be a dealer and will sell the high-quality items at retail to collectors, while the father is selling to dealers at wholesale.

So, in summary, let’s call this method of collecting what it is: Investing. There is nothing dishonorable about it. It can even be as enjoyable to the collector as collecting for pleasure. But I feel that investors have to go into that pursuit with eyes wide open; not with hope, prayer and assumptions about what ought to happen when they get ready to sell.

As with any financial transaction where entrepreneurs are hoping to make a profit, it is a tough world out there. Willing buyers at your price can be a good deal more scarce than you hoped. People not willing to pay your price are not necessarily stupid, crooked or hard-hearted. They are steely-eyed realists. And you need to be too.

Should you wish to comment on this column, or have questions or ideas you would like to have explored in a future column, please write to John Hotchner, VSC Contributor, P.O. Box 1125, Falls Church, VA 22041-0125, or email, putting “VSC” in the subject line.

Or comment right here.