by John M. Hotchner

The hunter dreams of a 14-point buck! The stamp collector has equally desirable quarry, and the hunting ground is at any nearby stamp show!

The eight-day international show in New York in 2016 was a

lollapalooza of an

event; a familiar

local show on steroids; with more

than 200 dealers

from around the

world to serve the

tastes of collectors from beginner status to the most discriminating specialist. As one somewhere in the middle of that pack, I was worried that the dealer community would have only expensive material because of the high booth fees an international show commands. I needn’t have been concerned. There was plenty of moderately priced material for all of us without bottomless wallets.

The eight-day international show in New York in 2016 was a

lollapalooza of an

event; a familiar

local show on steroids; with more

than 200 dealers

from around the

world to serve the

tastes of collectors from beginner status to the most discriminating specialist. As one somewhere in the middle of that pack, I was worried that the dealer community would have only expensive material because of the high booth fees an international show commands. I needn’t have been concerned. There was plenty of moderately priced material for all of us without bottomless wallets.

My shopping time was limited by other activities, but over the last three days I got in about six hours of digging through the stocks of a dozen or so dealers.

At every show I go to I hope to make one good find to add to my collection; something that is a combination of good price and interesting item that I can enjoy for years afterward. Often enough, it doesn’t happen (no great items, or a great item at too high a price), but the search is fun, and almost always something of interest will be found to make it worthwhile.

At the New York show two items came my way, and the rest of this column will be devoted to one of them because I am certain there are more examples “out there” waiting to be found.

Poking through the U.S. cover stock of a dealer from another country, I saw a cut square with the dollar values of the 1938 Prexie series, priced at $35. Cancelled in New York City on February 8 of a year that is unclear, it is shown in Figure 1. Given that the catalogue values of the three used stamps is $7, I hesitated. The combination is unusual, but 5x catalog unusual?

Poking through the U.S. cover stock of a dealer from another country, I saw a cut square with the dollar values of the 1938 Prexie series, priced at $35. Cancelled in New York City on February 8 of a year that is unclear, it is shown in Figure 1. Given that the catalogue values of the three used stamps is $7, I hesitated. The combination is unusual, but 5x catalog unusual?

Taking a closer look, the first thing to be noticed was that the $2 is a nice color misregistration. I like to find the heads of the dollar value Prexies misregistered in one direction or another, and the $2 is the hardest to find. On this one the vignette is quite far to the left; which would not please Republican Pres. Warren G. Harding, who is pictured on the stamp.

Next was noticing that the Calvin Coolidge head on the $5 was low on that stamp. At about this time, I concluded that the $35 asking price was reasonable, and I reached for my wallet.

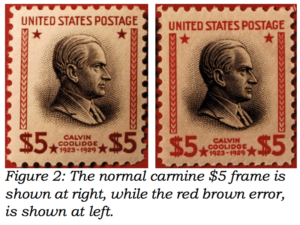

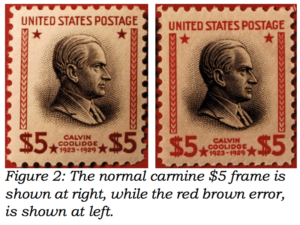

But wait — something about that $5 rang a bell. The reddish frame color was much darker than the normal “carmine” noted in the Scott Catalogue. Having seen this before on mint $5 examples submitted for expertizing, my mind’s eye pictured a reference photo I had been given by the late Joseph Thompson, who was a scholar in this realm. The photo is shown in Figure 2.

But wait — something about that $5 rang a bell. The reddish frame color was much darker than the normal “carmine” noted in the Scott Catalogue. Having seen this before on mint $5 examples submitted for expertizing, my mind’s eye pictured a reference photo I had been given by the late Joseph Thompson, who was a scholar in this realm. The photo is shown in Figure 2.

Could the $5 on this cut square be the rather rare “red brown” error that is listed in Scott’s? For $35 I was more than willing to take a chance until I could get it home and check my reference material.

Fast-forward a week, and I am pleased to say that the variety checks out. It appears to be what Scott calls No. 834a, red brown and black, mint value (never hinged) $2750; used in period, $7000. It only remains to have it expertized.

What is the story to this stamp, and why is the used value so much higher than the mint? A dive into my files provides considerable detail, which I will summarize below based on several articles from the philatelic press, auction listings, and a Thompson article* from The United States Specialist, monthly magazine of the United States Stamp Society.

All telling of the story of the #834a agree that the first reports of the error in the trade are attributed to U.S. expert and philatelic columnist (for Mekeel’s) George B. Sloane, in about 1947. He sent one on approval to a potential buyer in 1951 (asking price $75), writing the following note:

“I thought you would like to see the stamp. It was a comparatively small lot — about 90 stamps (most in blocks). I have held them up for almost four years but no more have shown up. It is my opinion that the stamp will continue to advance…. The color is definite and marked.”

Sloane had queried the Bureau of Engraving and Printing, the printer of these stamps, in 1950, and provided samples. He received a detailed response, dated April 18, 1950. Its essence is summarized by the following excerpt:

“…Stamps having the approximate color of these [submitted] stamps can result from either of two fundamentally different causes. Such stamps could have been produced at the time of printing in this bureau if the ink had become contaminated with minute quantities of black ink or carbon black… The second possible cause for the color of such stamps arises from the fact that the ink used in printing the border of these stamps contains certain components which darken perceptibly in the presence of a chemical… The bureau receives numerous inquiries concerning similar color changes in stamps in which it is apparent that these changes are produced by chemical treatment or by storage in the presence of certain gaseous chemicals after the stamps have left this bureau. Laboratory tests showed that five-dollar Coolidge stamps can be changed in color by chemicals so as to form an almost perfect visual color match with the stamps obtained from you…”

The letter goes on to explain that the submitted stamps were tested and determined to be unaltered by chemicals; thus a genuine variety.

Sloane’s report is, however, not the first sighting of this error. In the cited U.S. Specialist article, Thompson and Gill provide information on the first find of these stamps. They were first discovered by postal clerk Ralph Davis, who was also a well-known and respected philatelist from northern Virginia. He reported the purchase of two plate blocks of the error in 1938-39, at the post office where he worked. Given his status, he could not make a philatelic splash about his find, but he noted that other copies of the error were sold over the counter before it was noticed, identified and reported to postal authorities.

Davis told Thompson and Gill that “…over a million dollars’ worth of stamps of the error of color were recalled and destroyed when they were discovered.” This equates to 2,000 panes of 100 stamps with each pane containing one plate block.

As to numbers that got into philatelic hands, Thompson and Gill stated, “Since Davis said the error was sold over the counter before it was discovered, there could be any number of errors in existence. We have heard of only two canceled copies, about 100 mint singles, and nine plate blocks, although more may exist.”

So, with this background, could the Figure 1 cut square contain a genuine 834a? I would offer the following observations. The year in the cancellation cannot be determined. It would have to be 1939 or after.

The New York usage could be from the Davis find, or the Sloane find. Sloane was based in New York, but some of the undetermined number of $5 errors sold in northern Virginia could also have migrated to New York. And those purchased at Ralph Davis’ post office would likely not have been identified as anything special.

In addition I would posit that anyone trying to make examples of this error by chemically altering normal copies would identify the product as the error, so as to sell it at a premium. That clearly is not the case with the Figure 1 cut square.

Finally, chemical alterations generally affect more than just the intended color. In this case, the paper would also be altered in color. And the ultraviolet (UV) properties of the paper will also differ from normal.

Again, after inspection under 30x magnification, and with both longwave and shortwave UV, I can say that neither is the case here.

My conclusion is that there is every likelihood that the Figure 1 example is genuine. I will submit it for expertizing, and report the results here once I have received the opinion.

My conclusion is that there is every likelihood that the Figure 1 example is genuine. I will submit it for expertizing, and report the results here once I have received the opinion.

Addendum: The Philatelic Foundation found that the stamp “is not Scott 834a, rather it is a Scott 834, carmine and black, the carmine color oxidized.” PF did not provide any information as to how they reached that conclusion.

*Thompson, Joseph S., Jr. and Gill, Norma E., “The $5 Coolidge Error of Color,” The United States Specialist, July, 1990, pp 399-410. Published by The United States Stamp Society.

Should you wish to comment on this column, or have questions or ideas you would like to have explored in a future column, please write to John Hotchner, VSC Contributor, P.O. Box 1125, Falls Church, VA 22041-0125, or email, putting “VSC” in the subject line.

Or comment right here.

Move over chocolate – wine has become the guilty pleasure of choice this Easter according to new Australia Post research.

Move over chocolate – wine has become the guilty pleasure of choice this Easter according to new Australia Post research. “Our research showed almost half of survey respondents want to buy their Easter gifts online to avoid crowds, while a further 43 per cent said online shopping was quicker and easier.

“Our research showed almost half of survey respondents want to buy their Easter gifts online to avoid crowds, while a further 43 per cent said online shopping was quicker and easier.

COMPEX 2018 will be held on its new weekend of June 1, 2, and 3, and new location at Guerin College Prep, a large high school facility located at 8001 West Belmont Avenue, River Grove, IL 60171. River Grove is an adjacent suburb of Chicago on the northwest side. This location is easily reached by major roadways and public transportation and is about 6 miles from O’Hare Airport. Also, Guerin College Prep has a large parking lot (free, of course!) and the building is air conditioned!!!

COMPEX 2018 will be held on its new weekend of June 1, 2, and 3, and new location at Guerin College Prep, a large high school facility located at 8001 West Belmont Avenue, River Grove, IL 60171. River Grove is an adjacent suburb of Chicago on the northwest side. This location is easily reached by major roadways and public transportation and is about 6 miles from O’Hare Airport. Also, Guerin College Prep has a large parking lot (free, of course!) and the building is air conditioned!!! 27th March 2018 — Australia Post is releasing a commemorative stamp to celebrate the upcoming Gold Coast 2018 Commonwealth Games.

27th March 2018 — Australia Post is releasing a commemorative stamp to celebrate the upcoming Gold Coast 2018 Commonwealth Games. Australia Post Philatelic Manager, Michael Zsolt said: “this stamp issue commemorates the largest sporting event Australia has played host to this decade.”

Australia Post Philatelic Manager, Michael Zsolt said: “this stamp issue commemorates the largest sporting event Australia has played host to this decade.” Commonwealth Games in Glasgow.

Commonwealth Games in Glasgow. Coast landscape. It features the figures of three athletes; a gymnast, a hurdler and a swimmer, which aim to reflect the depth of heritage and deep humanity of the Games. For more information visit

Coast landscape. It features the figures of three athletes; a gymnast, a hurdler and a swimmer, which aim to reflect the depth of heritage and deep humanity of the Games. For more information visit  The Gold Coast 2018 Commonwealth Games stamp issue is available from 20 March 2018 at participating Post Offices, via mail order on 1800 331 794 and

The Gold Coast 2018 Commonwealth Games stamp issue is available from 20 March 2018 at participating Post Offices, via mail order on 1800 331 794 and  The Hague, 26 March 2018 – This year, two typically Dutch bridges in Dedemsvaart and Edam are the central features of PostNL’s postage stamp entries in the European design competition ‘EUROPA Stamp Best Design Competition’. This annual competition between European postal operators always has a common theme. For 2018, the theme is bridges.

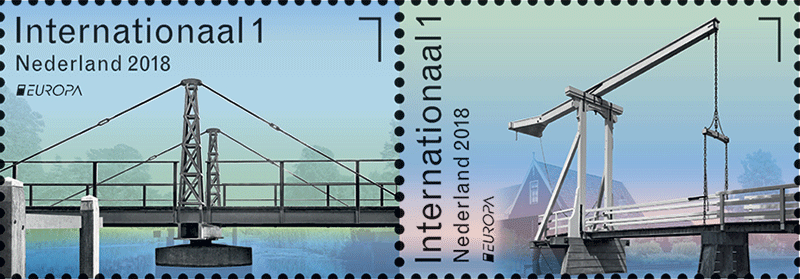

The Hague, 26 March 2018 – This year, two typically Dutch bridges in Dedemsvaart and Edam are the central features of PostNL’s postage stamp entries in the European design competition ‘EUROPA Stamp Best Design Competition’. This annual competition between European postal operators always has a common theme. For 2018, the theme is bridges. The wrought iron swing bridge in Dedemsvaart has a wooden bridge deck and is supported by ashlar stone abutments and a pillar. The bridge is a rare example of a nineteenth century swing bridge over the Dedemsvaart canal. The second bridge, the Kwakelbrug in Edam, is a narrow wooden drawbridge originating from the eighteenth century. The bridge is located at the end of the Scheepmakersdijk and connects to the Boerenverdriet. ‘Since the Netherlands has a vast amount of water, we also have a vast amount of bridges,’ says Stephan van de Eijnden, marketing director for Mail at PostNL. ‘What stands out for me is how typically Dutch these bridges are.’ Simple and plain, but often ingenious constructions to facilitate transport over water and land. The two bridges on these stamps are prime examples of this.’

The wrought iron swing bridge in Dedemsvaart has a wooden bridge deck and is supported by ashlar stone abutments and a pillar. The bridge is a rare example of a nineteenth century swing bridge over the Dedemsvaart canal. The second bridge, the Kwakelbrug in Edam, is a narrow wooden drawbridge originating from the eighteenth century. The bridge is located at the end of the Scheepmakersdijk and connects to the Boerenverdriet. ‘Since the Netherlands has a vast amount of water, we also have a vast amount of bridges,’ says Stephan van de Eijnden, marketing director for Mail at PostNL. ‘What stands out for me is how typically Dutch these bridges are.’ Simple and plain, but often ingenious constructions to facilitate transport over water and land. The two bridges on these stamps are prime examples of this.’ The design of the stamps is based on photos taken by Karen Polder herself when she visited the bridges. When editing the photographs, she made the background thin and transparent and the bridges black and white. ‘Both bridges have a very linear, constructive character,’ says Polder. ‘They’re not enormous bridges – they have slender, modest constructions. The locations of the two bridges differ drastically. The location in Edam is busy and colourful, whereas tranquility and nature predominate in Dedemsvaart. This distinction is reflected in the colour blocks used for the diffuse background.

The design of the stamps is based on photos taken by Karen Polder herself when she visited the bridges. When editing the photographs, she made the background thin and transparent and the bridges black and white. ‘Both bridges have a very linear, constructive character,’ says Polder. ‘They’re not enormous bridges – they have slender, modest constructions. The locations of the two bridges differ drastically. The location in Edam is busy and colourful, whereas tranquility and nature predominate in Dedemsvaart. This distinction is reflected in the colour blocks used for the diffuse background. Availability

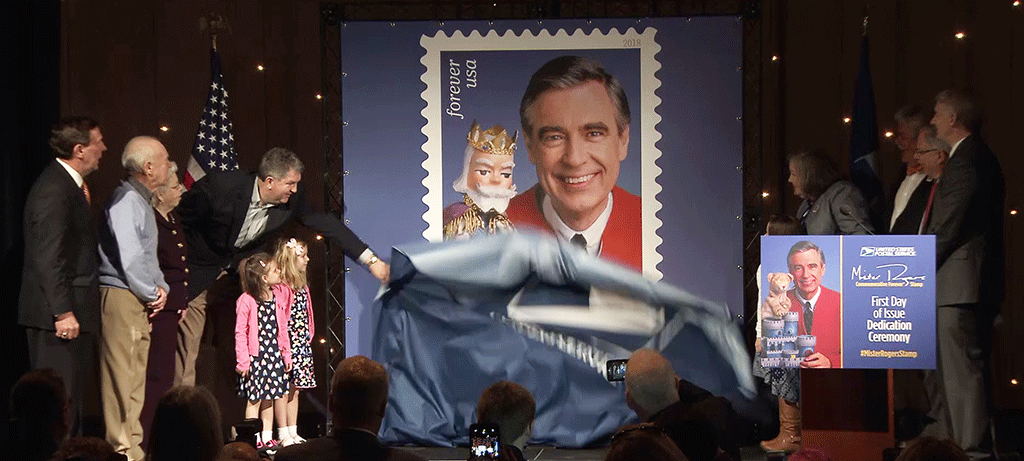

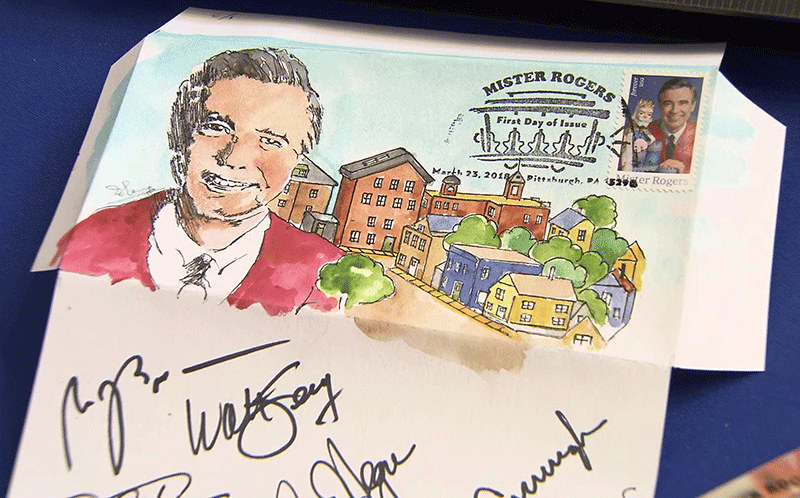

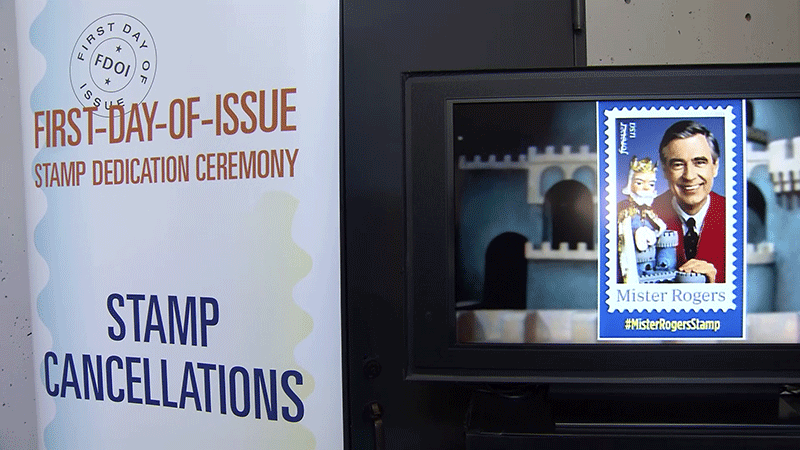

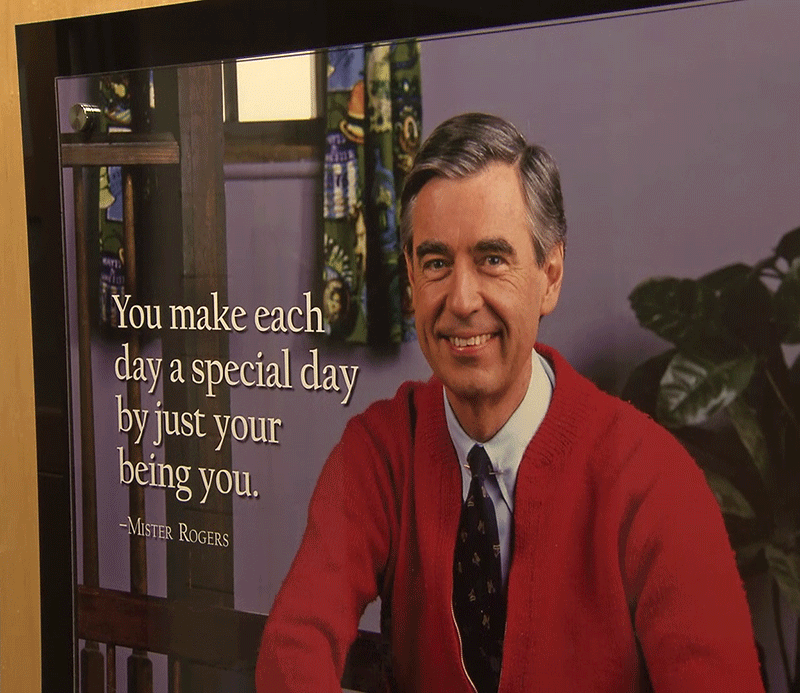

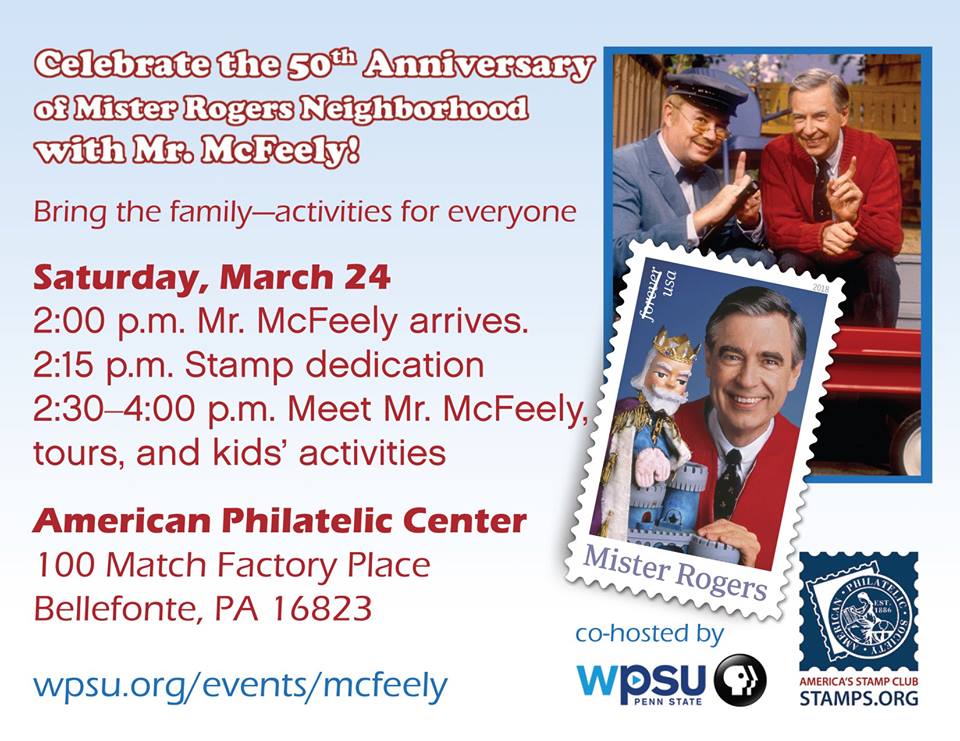

Availability The unveiling of the stamp. Video grab from USPS video.

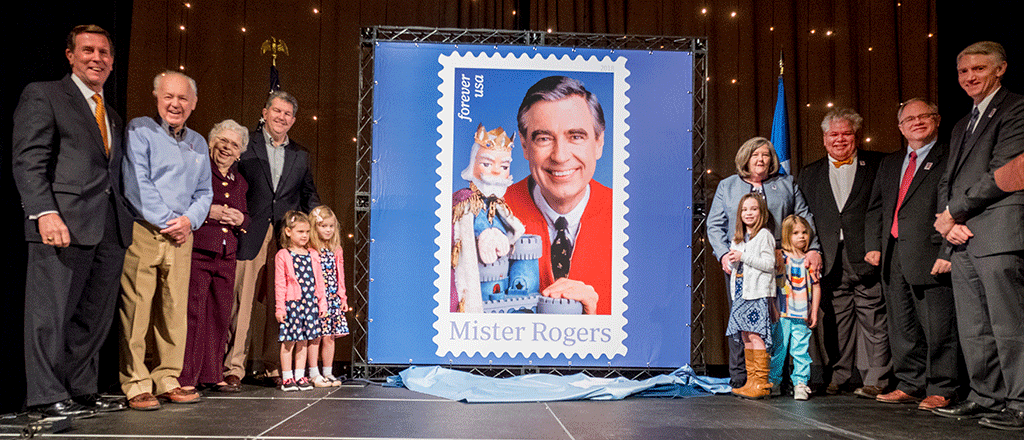

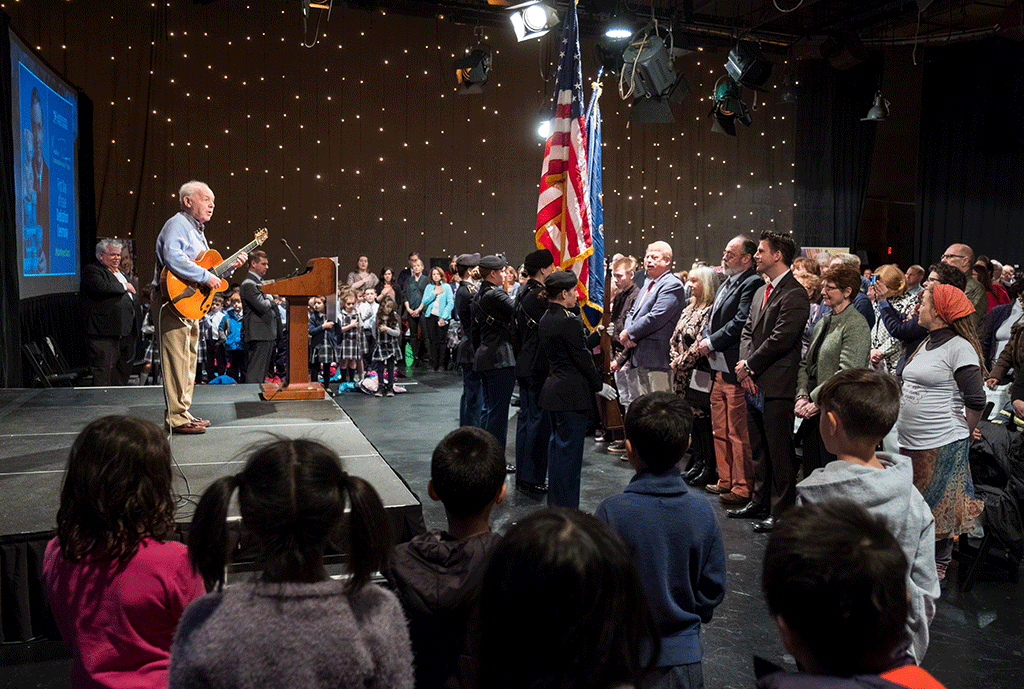

The unveiling of the stamp. Video grab from USPS video.  After the unveiling, left to right: James R. Okonak, Executive Director McFeely-Rogers Foundation; Joseph Negri, Adjunct Professor Jazz Guitar, Mary Pappert School of Music, Duquesne University, and “Handyman Negri” and the proprietor of Negri’s Music Store in Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood; Joanne Rogers, wife of Fred Rogers; former Postmaster General Patrick Donahue with his granddaughters, Charlotte and Lucy Donahoe; Meagan J. Brennan, current Postmaster General and Chief Executive Officer, United States Postal Service with her nieces Jamie and Jenna Masten; Master of Ceremonies Rick Sebak, WQED Multimedia; Jim Cunningham, Artistic Director, WQED-FM; Paul Siefken, President and CEO, The Fred Rogers Company. Photo by Daniel Afzal of the USPS.

After the unveiling, left to right: James R. Okonak, Executive Director McFeely-Rogers Foundation; Joseph Negri, Adjunct Professor Jazz Guitar, Mary Pappert School of Music, Duquesne University, and “Handyman Negri” and the proprietor of Negri’s Music Store in Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood; Joanne Rogers, wife of Fred Rogers; former Postmaster General Patrick Donahue with his granddaughters, Charlotte and Lucy Donahoe; Meagan J. Brennan, current Postmaster General and Chief Executive Officer, United States Postal Service with her nieces Jamie and Jenna Masten; Master of Ceremonies Rick Sebak, WQED Multimedia; Jim Cunningham, Artistic Director, WQED-FM; Paul Siefken, President and CEO, The Fred Rogers Company. Photo by Daniel Afzal of the USPS.

Joanne Rogers, Fred’s widow. Photo by Daniel Afzal of the USPS.

Joanne Rogers, Fred’s widow. Photo by Daniel Afzal of the USPS.

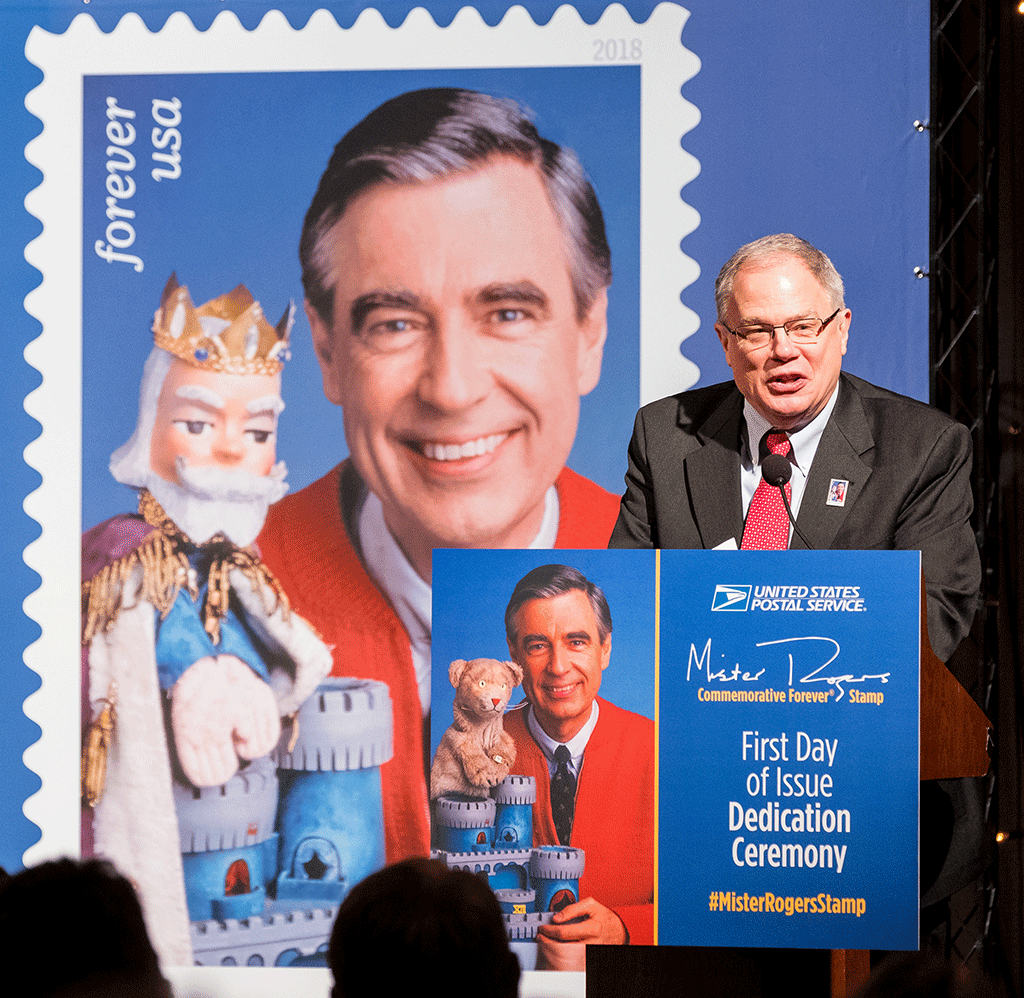

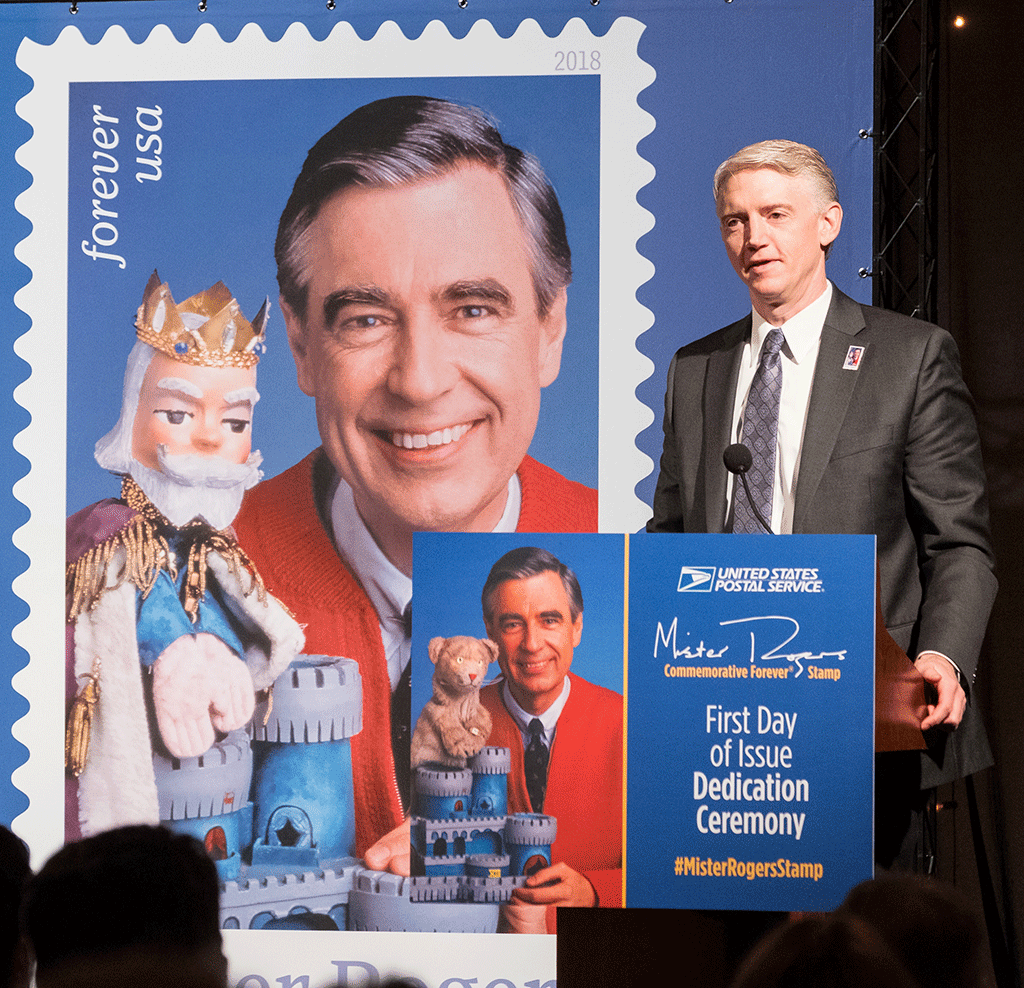

Paul Siefken, President and CEO, The Fred Rogers Company. Photo by Daniel Afzal of the USPS.

Paul Siefken, President and CEO, The Fred Rogers Company. Photo by Daniel Afzal of the USPS.

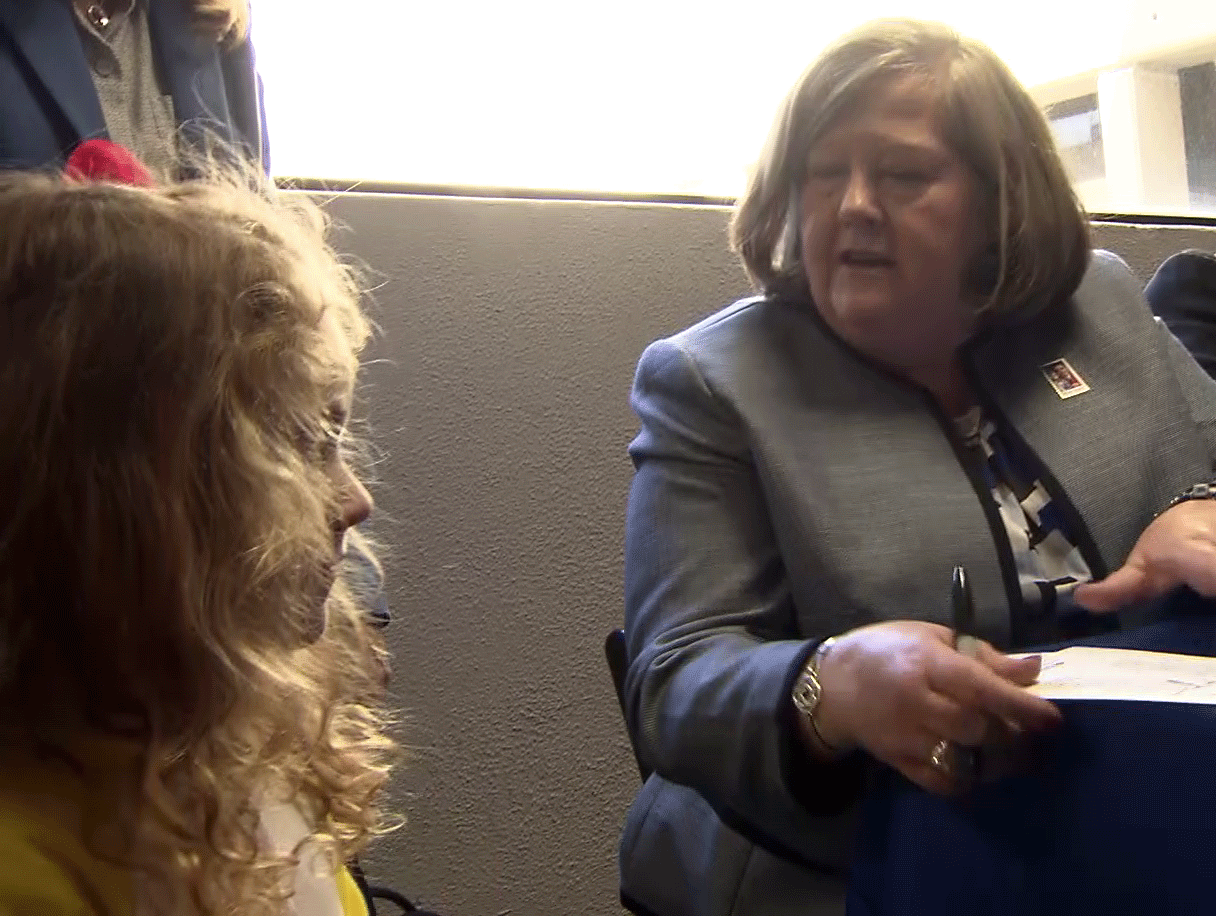

Postmaster General Megan Brennan. Video grab from USPS video.

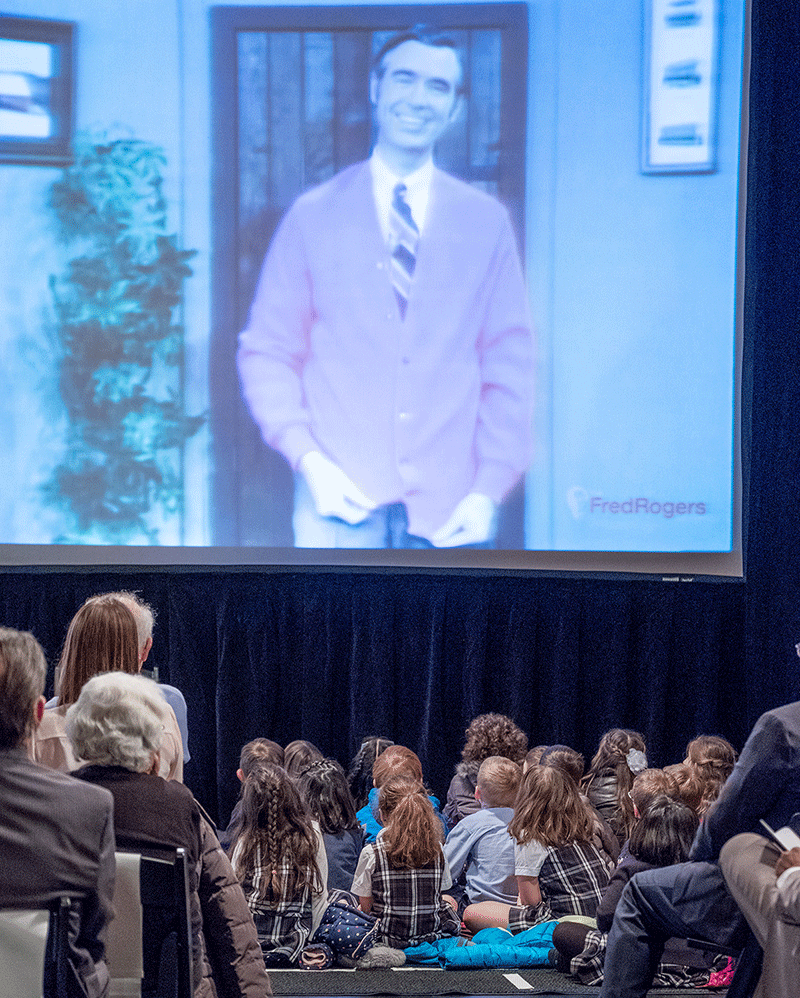

Postmaster General Megan Brennan. Video grab from USPS video. The audience, including students from the Fanny Edel Falk Laboratory School at the University of Pittsburgh, watch the tribute video during the ceremony. Photo by Daniel Afzal of the USPS.

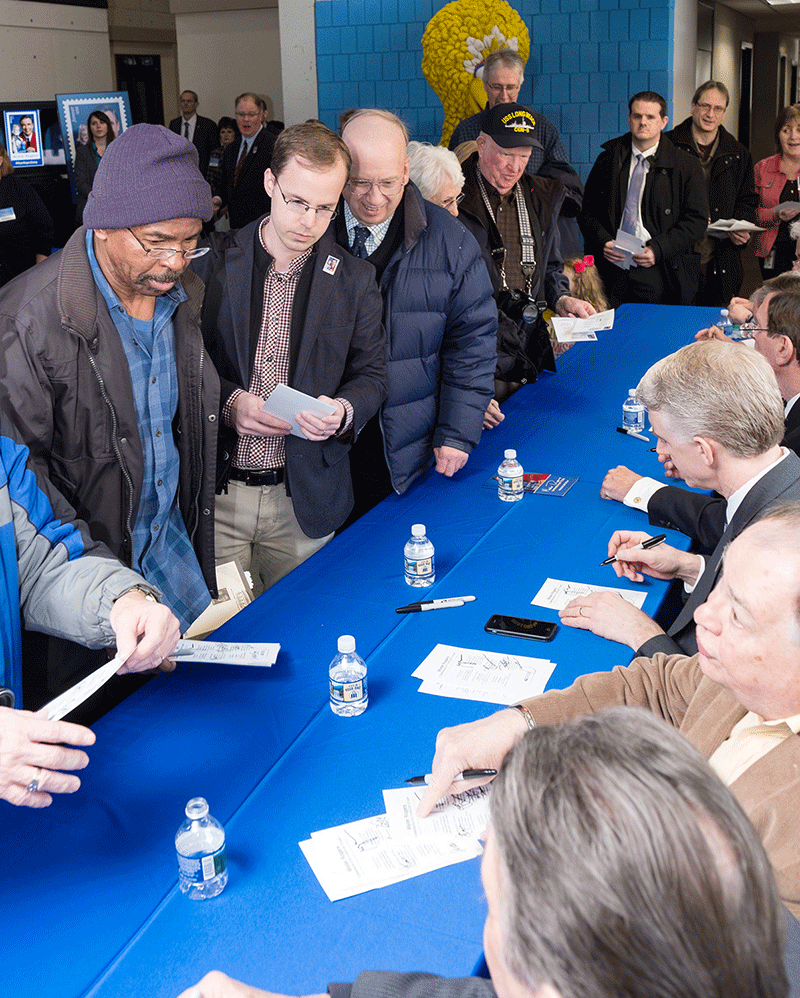

The audience, including students from the Fanny Edel Falk Laboratory School at the University of Pittsburgh, watch the tribute video during the ceremony. Photo by Daniel Afzal of the USPS. The autograph line after the cerremony. Second from left is Jay Bigalke, editor-in-chief of Linn’s Stamp News, and third from left is Foster Miller, membership chairman of the American First Day Cover Society. Photo by Daniel Afzal of the USPS.

The autograph line after the cerremony. Second from left is Jay Bigalke, editor-in-chief of Linn’s Stamp News, and third from left is Foster Miller, membership chairman of the American First Day Cover Society. Photo by Daniel Afzal of the USPS. Postmaster General Brennan signs an autograph for a young girl. Video grab from USPS video.

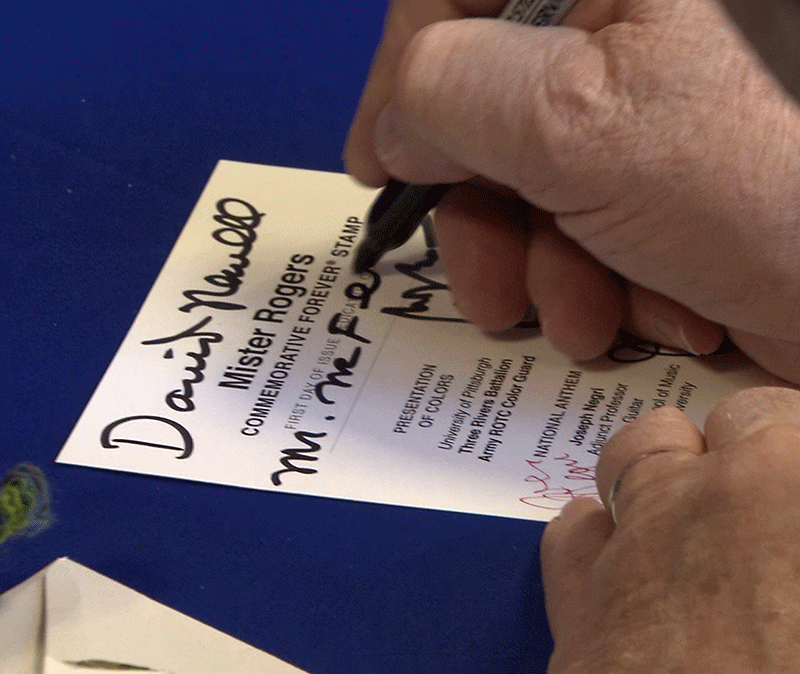

Postmaster General Brennan signs an autograph for a young girl. Video grab from USPS video.  David “Mr. McFeely” Newell signs an autograph. Video grab from USPS video.

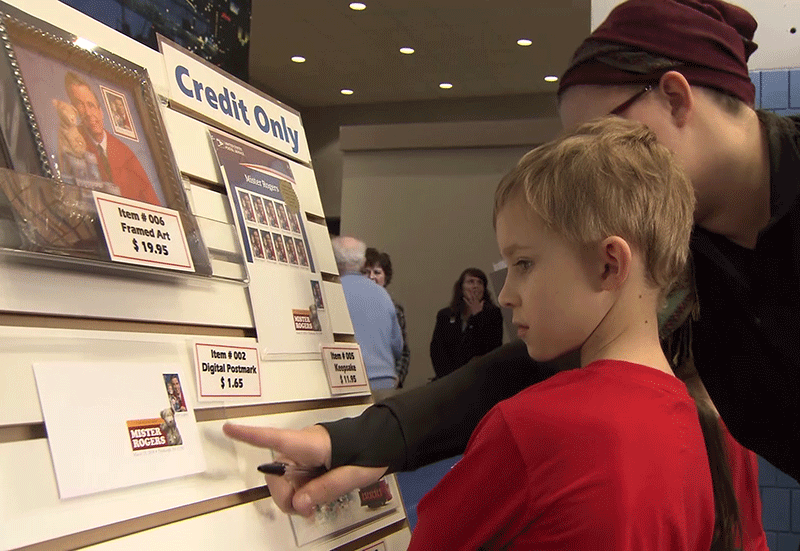

David “Mr. McFeely” Newell signs an autograph. Video grab from USPS video. A boy decides which Mister Rogers Stamp collectibles he wants. Video grab from USPS video.

A boy decides which Mister Rogers Stamp collectibles he wants. Video grab from USPS video. A postal clerk bags some purchases. Video grab from USPS video.

A postal clerk bags some purchases. Video grab from USPS video. Video grab from USPS video.

Video grab from USPS video. Video grab from USPS video.

Video grab from USPS video. Video grab from USPS video.

Video grab from USPS video. The entrance to the Mister Rogers Studio at WQED. Video grab from USPS video.

The entrance to the Mister Rogers Studio at WQED. Video grab from USPS video. The eight-day international show in New York in 2016 was a

lollapalooza of an

event; a familiar

local show on steroids; with more

than 200 dealers

from around the

world to serve the

tastes of collectors from beginner status to the most discriminating specialist. As one somewhere in the middle of that pack, I was worried that the dealer community would have only expensive material because of the high booth fees an international show commands. I needn’t have been concerned. There was plenty of moderately priced material for all of us without bottomless wallets.

The eight-day international show in New York in 2016 was a

lollapalooza of an

event; a familiar

local show on steroids; with more

than 200 dealers

from around the

world to serve the

tastes of collectors from beginner status to the most discriminating specialist. As one somewhere in the middle of that pack, I was worried that the dealer community would have only expensive material because of the high booth fees an international show commands. I needn’t have been concerned. There was plenty of moderately priced material for all of us without bottomless wallets. Poking through the U.S. cover stock of a dealer from another country, I saw a cut square with the dollar values of the 1938 Prexie series, priced at $35. Cancelled in New York City on February 8 of a year that is unclear, it is shown in Figure 1. Given that the catalogue values of the three used stamps is $7, I hesitated. The combination is unusual, but 5x catalog unusual?

Poking through the U.S. cover stock of a dealer from another country, I saw a cut square with the dollar values of the 1938 Prexie series, priced at $35. Cancelled in New York City on February 8 of a year that is unclear, it is shown in Figure 1. Given that the catalogue values of the three used stamps is $7, I hesitated. The combination is unusual, but 5x catalog unusual? But wait — something about that $5 rang a bell. The reddish frame color was much darker than the normal “carmine” noted in the Scott Catalogue. Having seen this before on mint $5 examples submitted for expertizing, my mind’s eye pictured a reference photo I had been given by the late Joseph Thompson, who was a scholar in this realm. The photo is shown in Figure 2.

But wait — something about that $5 rang a bell. The reddish frame color was much darker than the normal “carmine” noted in the Scott Catalogue. Having seen this before on mint $5 examples submitted for expertizing, my mind’s eye pictured a reference photo I had been given by the late Joseph Thompson, who was a scholar in this realm. The photo is shown in Figure 2. My conclusion is that there is every likelihood that the Figure 1 example is genuine. I will submit it for expertizing, and report the results here once I have received the opinion.

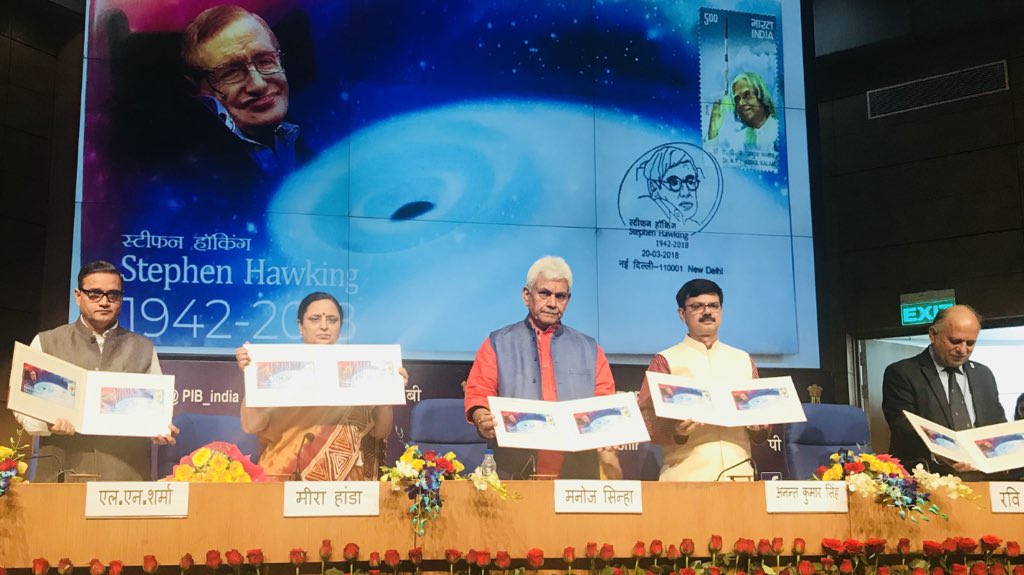

My conclusion is that there is every likelihood that the Figure 1 example is genuine. I will submit it for expertizing, and report the results here once I have received the opinion. India Post officials are shown in the photo unveiling the stamps.

India Post officials are shown in the photo unveiling the stamps.

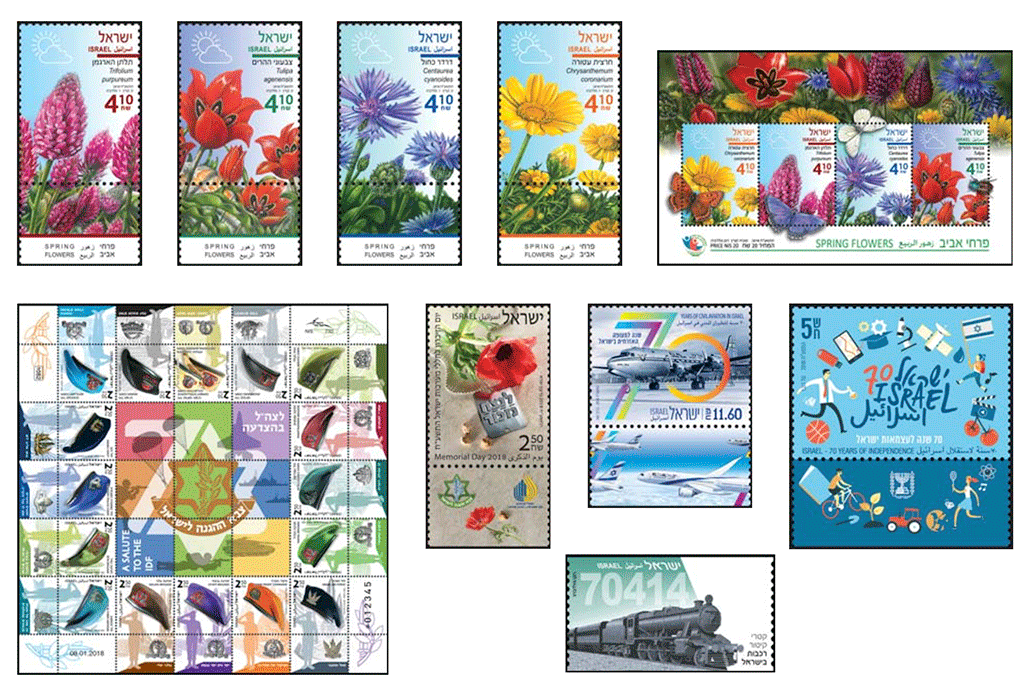

These stamps and the souvenir sheet will be issued April 9th. From Israel Post: The issue “reflects that season and the element of revival.

These stamps and the souvenir sheet will be issued April 9th. From Israel Post: The issue “reflects that season and the element of revival.