By John M. Hotchner

Most of us as collectors stay inside the philatelic box — standard collections of the United States or another country, or stay with an era like the first 100 years, or even a single issue  like the Liberty Series of 1954. Another group will focus on Back of the Book issues of one sort or another, or go the thematic route.

like the Liberty Series of 1954. Another group will focus on Back of the Book issues of one sort or another, or go the thematic route.

Going beyond the Scott Standard or U.S. Specialized Catalogues gets us to at least the outer edges of the box, but for such material there are often specialized catalogs that help us define boundaries. I’m talking here about such things as precancels, perfins, state revenues, and collecting specific plate numbers.

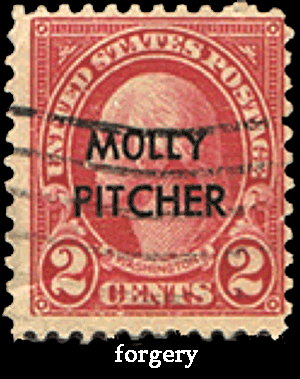

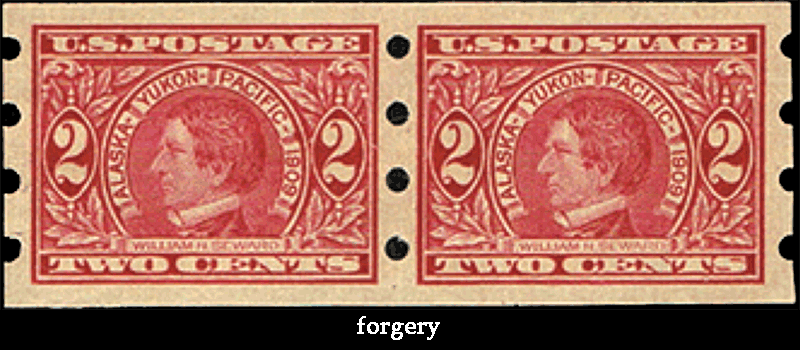

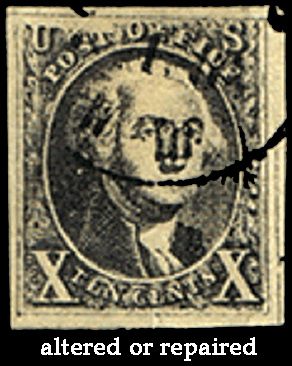

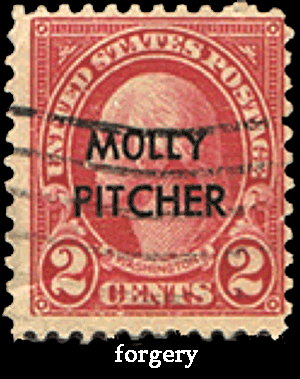

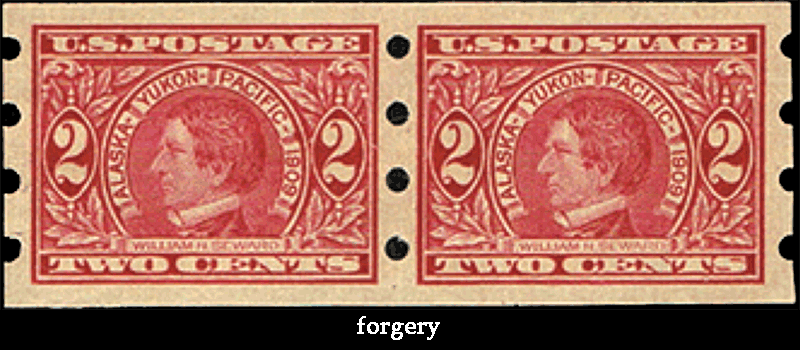

But if you want to bust out of the box completely, you have to dabble in something that has no catalog, and because of that, there are still many discoveries to be made. One such area is what I like to call Postal Larceny, which I define as the myriad ways in which individuals and sometimes organizations go about cheating the Postal Service of revenue,  using the post for illegal or immoral purposes, or attempting to fool collectors into buying altered stamps and covers, or outright forgeries.

using the post for illegal or immoral purposes, or attempting to fool collectors into buying altered stamps and covers, or outright forgeries.

I have found that to be a fascinating, challenging and enjoyable pursuit, and want to recommend it as a specialty all its own. Wait a minute: Aren’t postal forgeries — defined as “stamps” created to replicate genuine U.S. stamps, but fakes made to cheat the USPS out of revenue — listed in the Scott U.S. Specialized?

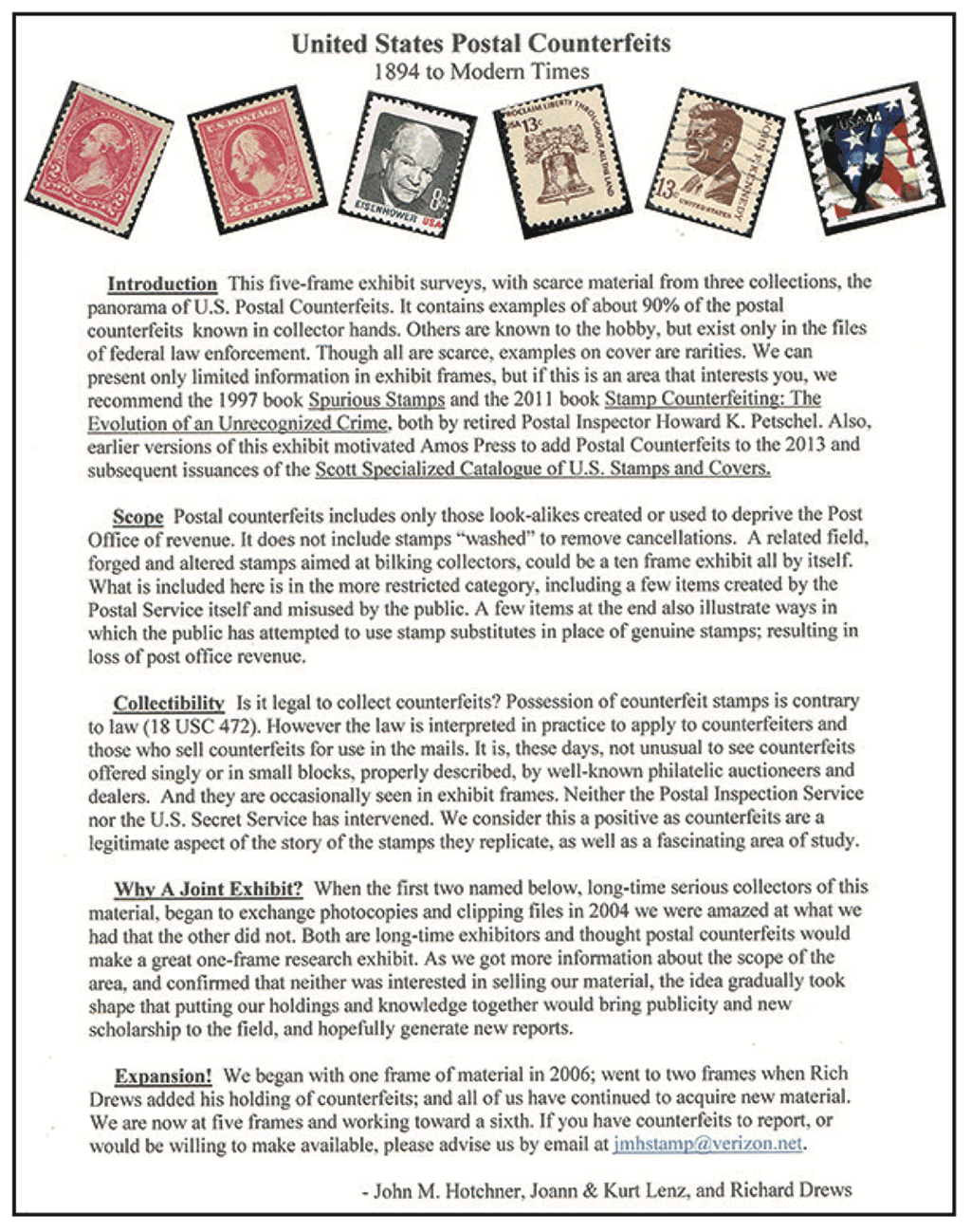

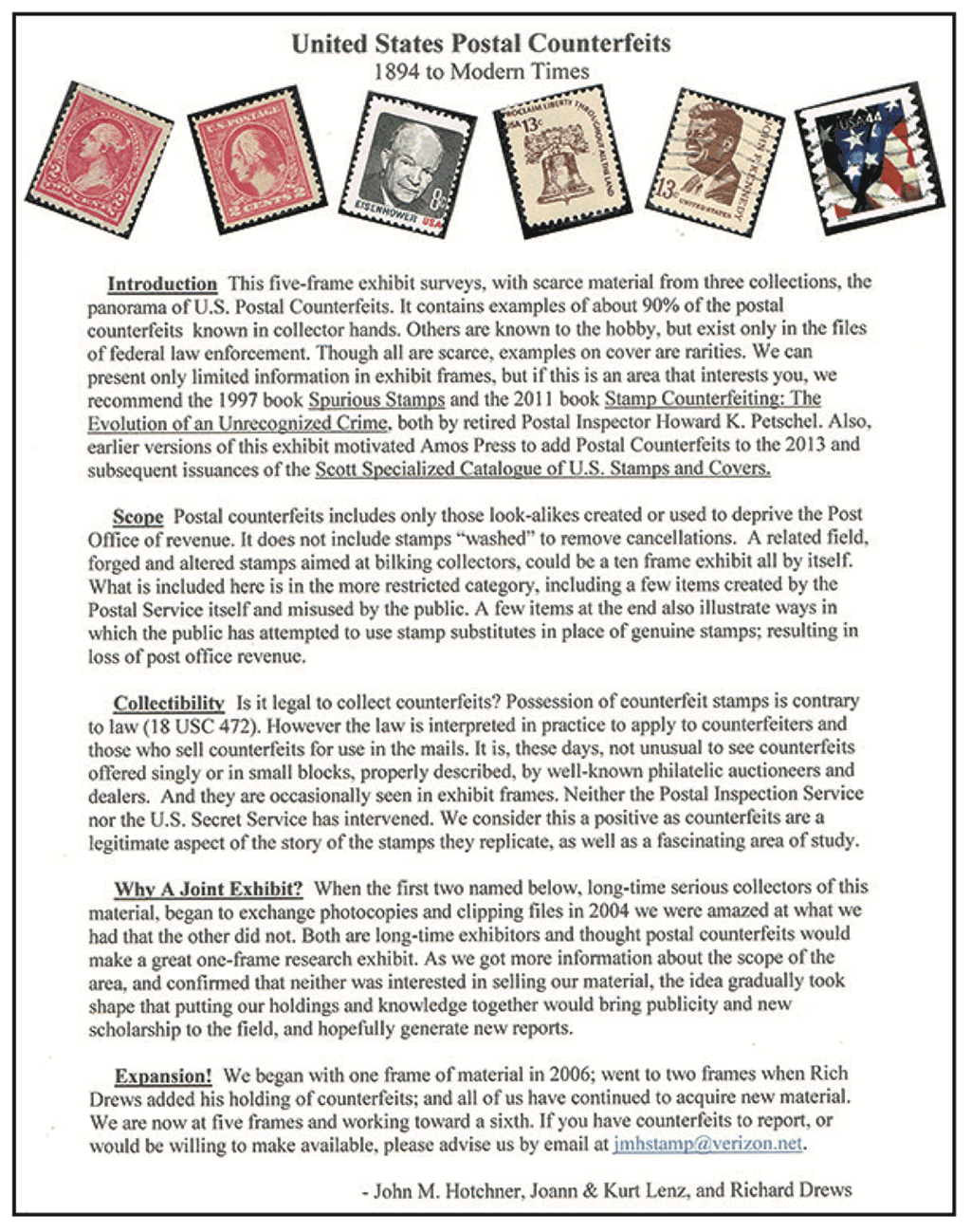

Yes, they are and have been since the 2013 catalogue. But when I began to collect them in the 1960s, there was no such resource. In fact there was no cohesive resource at all. Just after the turn of the new century, Rich Drews, Joann Lenz and I fortuitously discovered we all had the same interest. Each of us had a holding, and a file folder of clippings from the philatelic press about some of these counterfeits. None of us wanted to sell, so we hit on a scheme to pool our material and files. Each of us now has a complete file, though it by no means covers everything we own.

More importantly, we did an exhibit showing all of what we know to exist and have in “our” collection. See the title page on the right and also reproduced at the bottom of this page for clarity. While it began as two frames, it is now on the verge of a sixth, and the exhibit is shown at the APS Winter and Summer shows each year.

More importantly, we did an exhibit showing all of what we know to exist and have in “our” collection. See the title page on the right and also reproduced at the bottom of this page for clarity. While it began as two frames, it is now on the verge of a sixth, and the exhibit is shown at the APS Winter and Summer shows each year.

It was from viewing this exhibit that the Scott editors took the initiative in 2011 to come to us and ask if we would be interested in having a postal counterfeit section added to the Specialized — and if so, would we be interested in preparing it? Yes, and Yes, were the immediate answers.

Getting U.S. Postal Counterfeits within the box was a huge victory for us in that it gave form and recognition to the collecting area. But the area remains a challenge with both information and material waiting to be discovered. For example, there are Linn’s articles  describing a 20¢ Flag Over Supreme Court counterfeit that was used on mailed advertisements for pornography. We don’t have one, and indeed none of us have ever seen a genuine example!

describing a 20¢ Flag Over Supreme Court counterfeit that was used on mailed advertisements for pornography. We don’t have one, and indeed none of us have ever seen a genuine example!

The other aspect of postal counterfeits, if you follow the reports by Rudy de Mordaigle in U.S. Stamp News, and other philatelic press reports, is that the postal counterfeits business (for that is what it is!) has mushroomed in the years starting with the 37¢ Flag rate (2002). There have been more counterfeits since then than in all the years since 1894 when the first examples are recorded. And the quality of the newer counterfeits is very high. It used to be that counterfeiters had to replicate engraved U.S. stamps. No longer. The USPS changed their requirements to eliminate engraving in favor of photogravure, which is much less expensive. But it is also much easier to credibly fake.  So, where ‘in the olden days’ a postal employee might identify a counterfeit and call in the Inspectors, current counterfeits are well enough done that postal staff can not easily tell the difference between the fakes and genuine stamps without a magnifier.

So, where ‘in the olden days’ a postal employee might identify a counterfeit and call in the Inspectors, current counterfeits are well enough done that postal staff can not easily tell the difference between the fakes and genuine stamps without a magnifier.

Processing equipment can spot the counterfeits because most have no or the wrong tagging. But it seems that the equipment also kicks out envelopes with perfectly good stamps in sufficient numbers to make tracking each reject to see if it is a counterfeit not a realistic option.

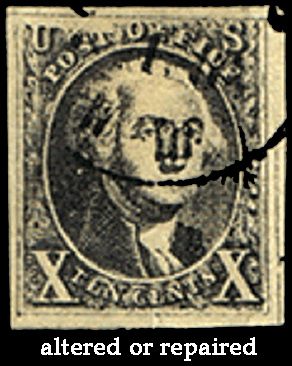

Virtually each new First Class or Forever definitive of the last 15 years has been counterfeited numerous times and by numerous sources. They are sold openly on the Internet and marketed to mom and pop stores in inner cities, and the USPS seems to be unable or unwilling to put a stop to it; thus adding hundreds of millions of dollars to the Postal Service deficit. This level of audacity is equaled if not exceeded by what have come to be called the “stamp doctors” who alter genuine U.S. stamps to make them into more expensive versions (making coils from imperf stamps, adding “Kans.” Or “Nebr.” Overprints, for example) and repair flawed stamps to make them more desirable (and thus more expensive). Examples of this practice might include reperfing to replace damaged perforations, adding perfs to straight edges, filling in pin holes, replacing hinged gum, and much, much more.

This level of audacity is equaled if not exceeded by what have come to be called the “stamp doctors” who alter genuine U.S. stamps to make them into more expensive versions (making coils from imperf stamps, adding “Kans.” Or “Nebr.” Overprints, for example) and repair flawed stamps to make them more desirable (and thus more expensive). Examples of this practice might include reperfing to replace damaged perforations, adding perfs to straight edges, filling in pin holes, replacing hinged gum, and much, much more.

Putting together a collection of faked, altered and repaired stamps is a challenge because no dealer specializes in such material, but almost every dealer will have some examples and they mostly sell for pennies on the catalogue-value dollar. The collector who accumulates and studies such material is bound to learn a great deal about the properties of such material, but will also have a leg up in being able to make good judgments about genuine and unaltered stamps.

Putting together a collection of faked, altered and repaired stamps is a challenge because no dealer specializes in such material, but almost every dealer will have some examples and they mostly sell for pennies on the catalogue-value dollar. The collector who accumulates and studies such material is bound to learn a great deal about the properties of such material, but will also have a leg up in being able to make good judgments about genuine and unaltered stamps.

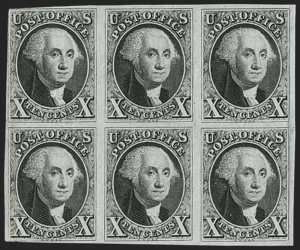

Throughout this article are examples of U.S. collector forgeries and altered or repaired stamps. I have purposely picked badly done examples that are obviously bad, but readers  should be warned that the art of forging, altering and repairing has made great strides in recent years, and the only reliable ways to avoid such material are by acquiring personal knowledge, and knowing how to use the services of a reputable expertizing organization.

should be warned that the art of forging, altering and repairing has made great strides in recent years, and the only reliable ways to avoid such material are by acquiring personal knowledge, and knowing how to use the services of a reputable expertizing organization.

We will end this column at this point, but I will continue in future columns. We will look at use of stamp-like substitutes for postage stamps, attempts at short payment, use of the mails for criminal activity, stolen mail, stamp washing to remove cancellations, postal stationery counterfeits, misuse of USPS stamp images, movie prop stamps, and more.

Should you wish to comment on this column, or have questions or ideas you would like to have explored in a future column, please write to John Hotchner, VSC Contributor, P.O. Box 1125, Falls Church, VA 22041-0125, or email, putting “VSC” in the subject line.

Or comment right here.

The U.S. plans to pull out of an international postal treaty, because it allows China to ship packages to the U.S. at discounted rates. That, according to the Administration, costs the U.S. Postal Service about $170 million a year.

The U.S. plans to pull out of an international postal treaty, because it allows China to ship packages to the U.S. at discounted rates. That, according to the Administration, costs the U.S. Postal Service about $170 million a year. ostal Service,” Jay Timmons, the president of the National Association of Manufacturers, said in a statement. “This outdated arrangement contributes significantly to the flood of counterfeit goods and dangerous drugs that enter the country from China.”

ostal Service,” Jay Timmons, the president of the National Association of Manufacturers, said in a statement. “This outdated arrangement contributes significantly to the flood of counterfeit goods and dangerous drugs that enter the country from China.”

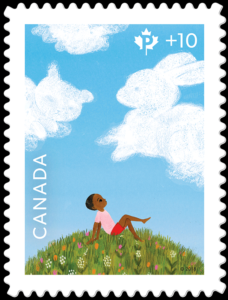

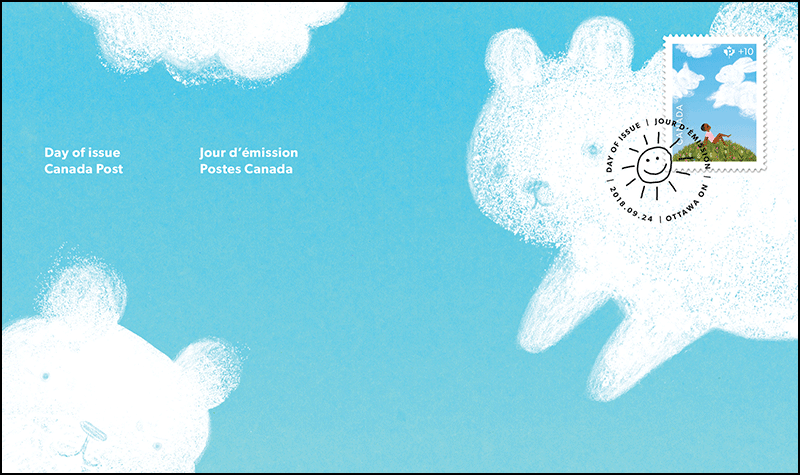

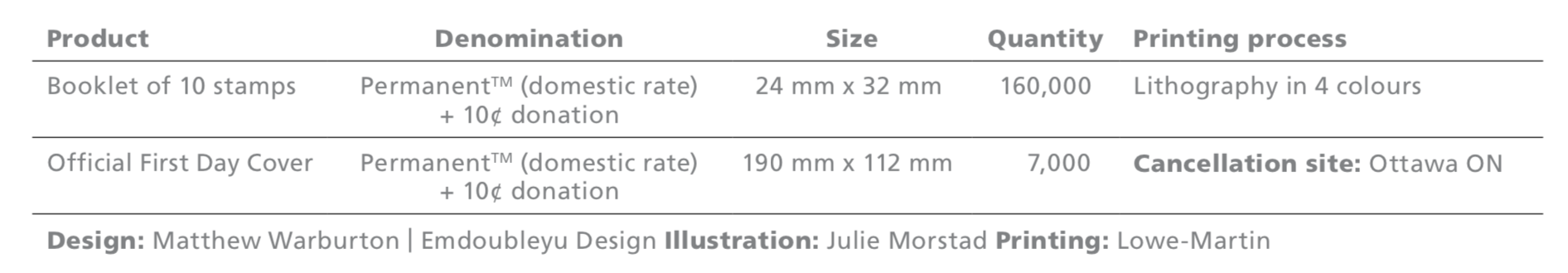

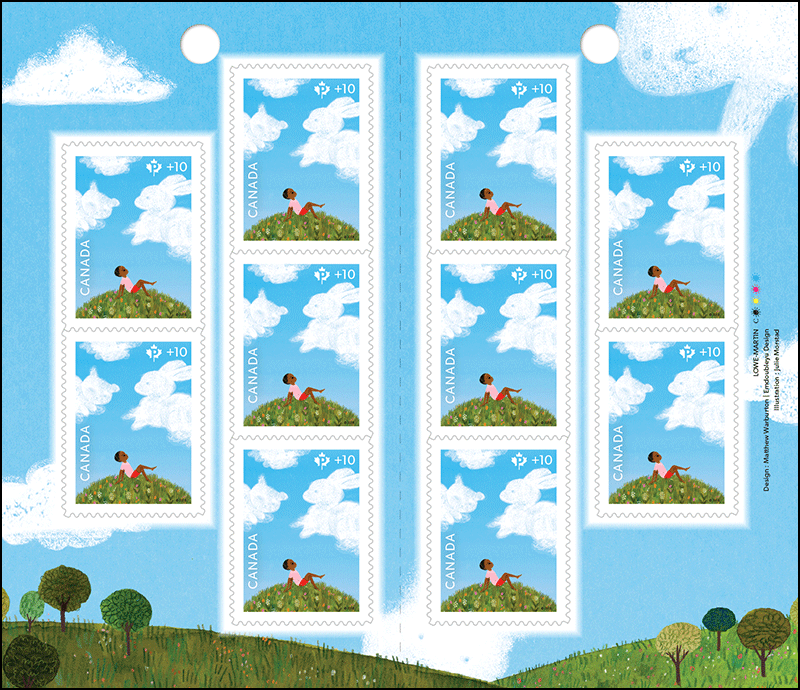

The release of the Canada Post Community Foundation’s fundraising semi-postal stamp signals the start of Canada Post’s annual fundraising campaign. Your dollar donation for a booklet of 10 stamps and 10 cents for the Official First Day Cover goes directly to support Canadian children and youth, through the funding of programs for breakfast, anti-bullying, special education, camps for children fighting illness, early literacy and other programs.

The release of the Canada Post Community Foundation’s fundraising semi-postal stamp signals the start of Canada Post’s annual fundraising campaign. Your dollar donation for a booklet of 10 stamps and 10 cents for the Official First Day Cover goes directly to support Canadian children and youth, through the funding of programs for breakfast, anti-bullying, special education, camps for children fighting illness, early literacy and other programs.

like the Liberty Series of 1954. Another group will focus on Back of the Book issues of one sort or another, or go the thematic route.

like the Liberty Series of 1954. Another group will focus on Back of the Book issues of one sort or another, or go the thematic route. using the post for illegal or immoral purposes, or attempting to fool collectors into buying altered stamps and covers, or outright forgeries.

using the post for illegal or immoral purposes, or attempting to fool collectors into buying altered stamps and covers, or outright forgeries. More importantly, we did an exhibit showing all of what we know to exist and have in “our” collection. See the title page on the right and also reproduced at the bottom of this page for clarity. While it began as two frames, it is now on the verge of a sixth, and the exhibit is shown at the APS Winter and Summer shows each year.

More importantly, we did an exhibit showing all of what we know to exist and have in “our” collection. See the title page on the right and also reproduced at the bottom of this page for clarity. While it began as two frames, it is now on the verge of a sixth, and the exhibit is shown at the APS Winter and Summer shows each year. describing a 20¢ Flag Over Supreme Court counterfeit that was used on mailed advertisements for pornography. We don’t have one, and indeed none of us have ever seen a genuine example!

describing a 20¢ Flag Over Supreme Court counterfeit that was used on mailed advertisements for pornography. We don’t have one, and indeed none of us have ever seen a genuine example! So, where ‘in the olden days’ a postal employee might identify a counterfeit and call in the Inspectors, current counterfeits are well enough done that postal staff can not easily tell the difference between the fakes and genuine stamps without a magnifier.

So, where ‘in the olden days’ a postal employee might identify a counterfeit and call in the Inspectors, current counterfeits are well enough done that postal staff can not easily tell the difference between the fakes and genuine stamps without a magnifier. This level of audacity is equaled if not exceeded by what have come to be called the “stamp doctors” who alter genuine U.S. stamps to make them into more expensive versions (making coils from imperf stamps, adding “Kans.” Or “Nebr.” Overprints, for example) and repair flawed stamps to make them more desirable (and thus more expensive). Examples of this practice might include reperfing to replace damaged perforations, adding perfs to straight edges, filling in pin holes, replacing hinged gum, and much, much more.

This level of audacity is equaled if not exceeded by what have come to be called the “stamp doctors” who alter genuine U.S. stamps to make them into more expensive versions (making coils from imperf stamps, adding “Kans.” Or “Nebr.” Overprints, for example) and repair flawed stamps to make them more desirable (and thus more expensive). Examples of this practice might include reperfing to replace damaged perforations, adding perfs to straight edges, filling in pin holes, replacing hinged gum, and much, much more. Putting together a collection of faked, altered and repaired stamps is a challenge because no dealer specializes in such material, but almost every dealer will have some examples and they mostly sell for pennies on the catalogue-value dollar. The collector who accumulates and studies such material is bound to learn a great deal about the properties of such material, but will also have a leg up in being able to make good judgments about genuine and unaltered stamps.

Putting together a collection of faked, altered and repaired stamps is a challenge because no dealer specializes in such material, but almost every dealer will have some examples and they mostly sell for pennies on the catalogue-value dollar. The collector who accumulates and studies such material is bound to learn a great deal about the properties of such material, but will also have a leg up in being able to make good judgments about genuine and unaltered stamps. should be warned that the art of forging, altering and repairing has made great strides in recent years, and the only reliable ways to avoid such material are by acquiring personal knowledge, and knowing how to use the services of a reputable expertizing organization.

should be warned that the art of forging, altering and repairing has made great strides in recent years, and the only reliable ways to avoid such material are by acquiring personal knowledge, and knowing how to use the services of a reputable expertizing organization.

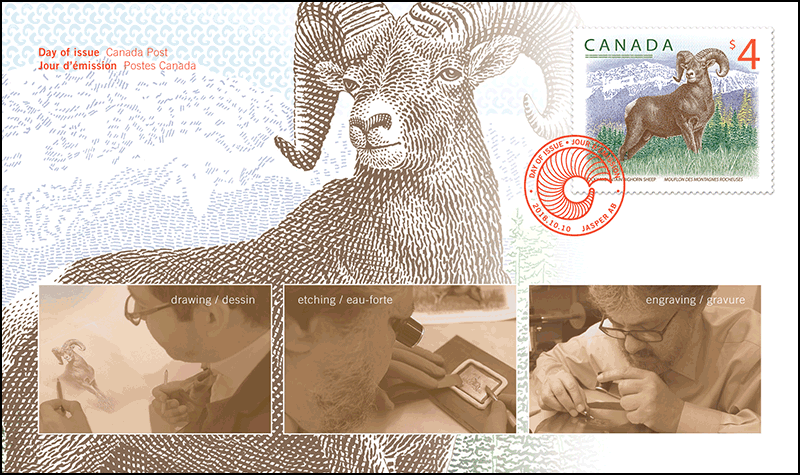

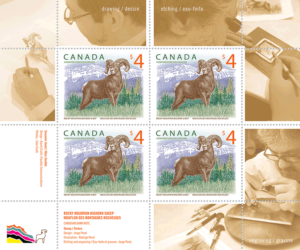

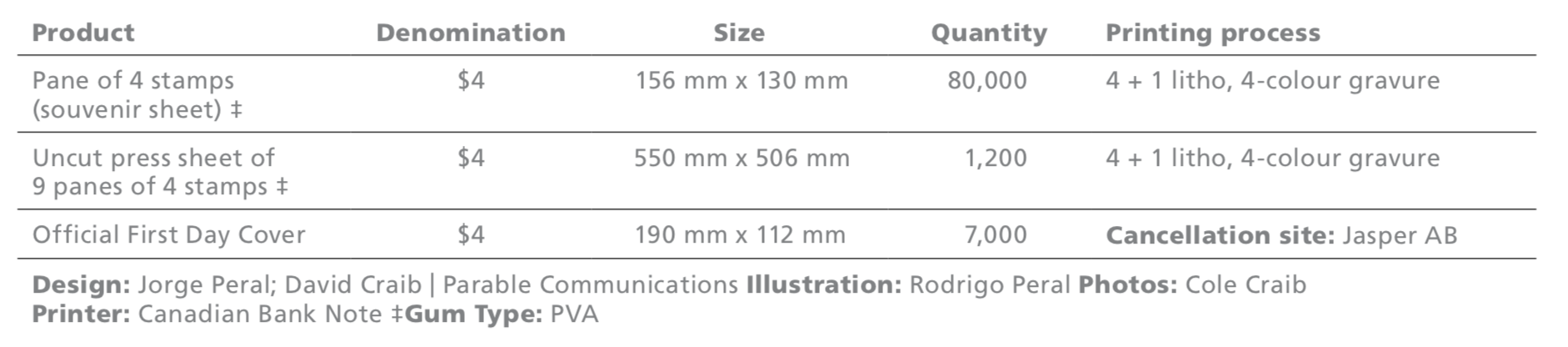

OTTAWA, Oct 10, 2018 – A legendary climber of the Rocky Mountains’ sheer crags pauses in a majestic pose on Canada Post’s newest large-format, high-value definitive stamp. Valued at $4, the stamp is part of an ongoing Canadian wildlife series.

OTTAWA, Oct 10, 2018 – A legendary climber of the Rocky Mountains’ sheer crags pauses in a majestic pose on Canada Post’s newest large-format, high-value definitive stamp. Valued at $4, the stamp is part of an ongoing Canadian wildlife series.

The stamps are available in a pane of four (souvenir sheet) (shown at right). Additional collectibles include an Official First Day Cover (OFDC) cancelled in Jasper, AB (shown above); a limited edition uncut press sheet with nine panes of four stamps signed by master engraver Jorge Peral (shown below); a framed and numbered lithographic print signed by illustrator Rodrigo Peral; and a framed enlargement of the stamp image, plus the actual stamp.

The stamps are available in a pane of four (souvenir sheet) (shown at right). Additional collectibles include an Official First Day Cover (OFDC) cancelled in Jasper, AB (shown above); a limited edition uncut press sheet with nine panes of four stamps signed by master engraver Jorge Peral (shown below); a framed and numbered lithographic print signed by illustrator Rodrigo Peral; and a framed enlargement of the stamp image, plus the actual stamp.

Ivan Cash is an award-winning interactive artist and film director, and the founder of

Ivan Cash is an award-winning interactive artist and film director, and the founder of  Spencer R. Crew is the

Spencer R. Crew is the  Mike Harrity is the senior associate athletics director, Student-Athlete Services, at the University of Notre Dame. He leads the areas of sports performance and student welfare and development, serves a lead role with primary benefactor groups.

Mike Harrity is the senior associate athletics director, Student-Athlete Services, at the University of Notre Dame. He leads the areas of sports performance and student welfare and development, serves a lead role with primary benefactor groups. WASHINGTON — The United States Postal Service filed notice with the Postal Regulatory Commission (PRC) today of price changes to take effect Jan. 27, 2019.

WASHINGTON — The United States Postal Service filed notice with the Postal Regulatory Commission (PRC) today of price changes to take effect Jan. 27, 2019. The Postal Service has some of the lowest letter mail postage rates in the industrialized world and also continues to offer a great value in shipping. Unlike some other shippers, the Postal Service does not add surcharges for fuel, residential delivery, or regular Saturday or holiday season delivery.

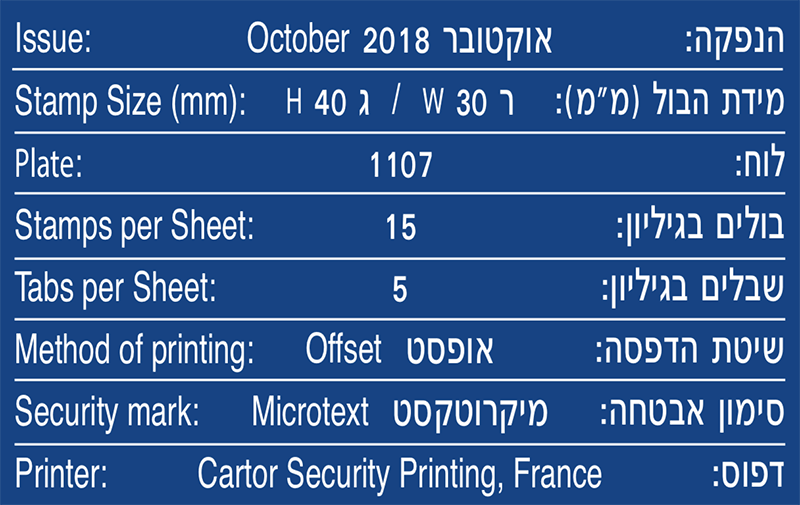

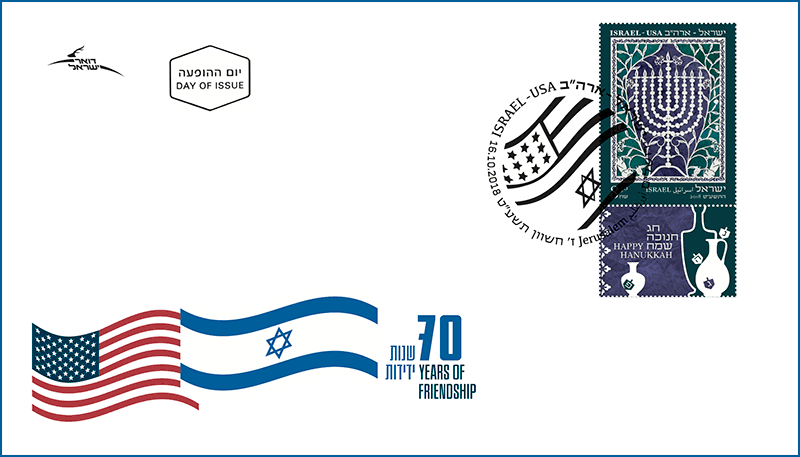

The Postal Service has some of the lowest letter mail postage rates in the industrialized world and also continues to offer a great value in shipping. Unlike some other shippers, the Postal Service does not add surcharges for fuel, residential delivery, or regular Saturday or holiday season delivery. [Issue date: October 16, 2018, same as the U.S. version. Details on the U.S. version are

[Issue date: October 16, 2018, same as the U.S. version. Details on the U.S. version are  In the year 167 BCE the Hellenistic king Antiochus IV forbade the Jewish residents of Eretz Israel to study the Torah and to perform the Jewish mitzvahs. Mattathias the Hasmonean and his sons led the people’s revolt against the cruel regime, and after harsh battles successfully freed Jerusalem and the Temple.

In the year 167 BCE the Hellenistic king Antiochus IV forbade the Jewish residents of Eretz Israel to study the Torah and to perform the Jewish mitzvahs. Mattathias the Hasmonean and his sons led the people’s revolt against the cruel regime, and after harsh battles successfully freed Jerusalem and the Temple.

A portion of financier Bill Gross’ stamp collection sold at auction Wednesday evening, October 3rd, for $10 million. That is a record for a single-day philatelic auction.

A portion of financier Bill Gross’ stamp collection sold at auction Wednesday evening, October 3rd, for $10 million. That is a record for a single-day philatelic auction.

5307 (50¢) Dragons – Green Dragon and Castle

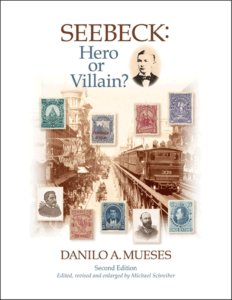

5307 (50¢) Dragons – Green Dragon and Castle The ebook is titled Seebeck: Hero or Villain? by Danilo A. Mueses.

The ebook is titled Seebeck: Hero or Villain? by Danilo A. Mueses.