Dealing With American Flags

by John M. Hotchner

With the presidential election behind us and the inauguration coming up, we are seeing the American Flag as the backdrop of much TV reporting. It got me wondering what might be found in the pantheon of American stamp issues that might make for an interesting way to give more depth to U.S. collecting. There is certainly nothing wrong with the traditional approach of collecting one of every U.S. stamp issued. And yet for many of us, new challenges beckon, and U.S. Flags is one that comes with a high level of knowledge, enthusiasm, and even offers a way to connect with non-collectors who have a love for America and its symbols.

With the presidential election behind us and the inauguration coming up, we are seeing the American Flag as the backdrop of much TV reporting. It got me wondering what might be found in the pantheon of American stamp issues that might make for an interesting way to give more depth to U.S. collecting. There is certainly nothing wrong with the traditional approach of collecting one of every U.S. stamp issued. And yet for many of us, new challenges beckon, and U.S. Flags is one that comes with a high level of knowledge, enthusiasm, and even offers a way to connect with non-collectors who have a love for America and its symbols.

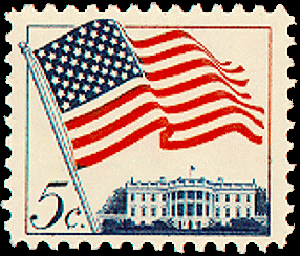

With the 1963 5¢ Flag Over White House (Scott #1208, right) issue, the U.S. Postal Service began an unbroken run of definitive (regular postage) stamps that extends to today. This movement really got into high gear with the issuance of the first plate number coil (18¢) Flag stamps in 1981. One of the post-1963 definitives (Scott #1891) is shown below.

With the 1963 5¢ Flag Over White House (Scott #1208, right) issue, the U.S. Postal Service began an unbroken run of definitive (regular postage) stamps that extends to today. This movement really got into high gear with the issuance of the first plate number coil (18¢) Flag stamps in 1981. One of the post-1963 definitives (Scott #1891) is shown below.

In the 1990s, the U.S. Postal Service contracted out the printing of more and more definitives to the private sector, and multiple  printers were needed to produce the multiple billions of Flag stamps needed by the public. Ultimately, the Bureau of Engraving and Printing (BEP) got out of printing U.S. stamps altogether in 2005. Multiple printers meant not just different plate numbers, but many different versions of each issue including: lick-and-stick, self-stick, tagging varieties, separation (perforation and die cut) varieties, print dates in the lower left corner, microprinting entries, slight design differences, and counting numbers on the back. Most of this is reflected in increasingly complex Scott U.S. Specialized Catalogue listings.

printers were needed to produce the multiple billions of Flag stamps needed by the public. Ultimately, the Bureau of Engraving and Printing (BEP) got out of printing U.S. stamps altogether in 2005. Multiple printers meant not just different plate numbers, but many different versions of each issue including: lick-and-stick, self-stick, tagging varieties, separation (perforation and die cut) varieties, print dates in the lower left corner, microprinting entries, slight design differences, and counting numbers on the back. Most of this is reflected in increasingly complex Scott U.S. Specialized Catalogue listings.

There is enough variety in the modern issues since the 1990s that there are collectors  specializing in a single definitive issue. I might also mention that there is the allied area of counterfeits that can be added. As the USPS transitioned from engraved designs to photogravure-produced designs, the incidence of credible postal counterfeits has gone up exponentially; and enforcement of the anti-counterfeiting statutes became a huge challenge. Today, armed with an ultraviolet detector, those collectors with access to quantities of modern definitives can find postal counterfeits easily because most are not tagged; and those that are, aren’t tagged properly. It seems that replicating the tagging is much more difficult and expensive for the criminal class than replicating the design!

specializing in a single definitive issue. I might also mention that there is the allied area of counterfeits that can be added. As the USPS transitioned from engraved designs to photogravure-produced designs, the incidence of credible postal counterfeits has gone up exponentially; and enforcement of the anti-counterfeiting statutes became a huge challenge. Today, armed with an ultraviolet detector, those collectors with access to quantities of modern definitives can find postal counterfeits easily because most are not tagged; and those that are, aren’t tagged properly. It seems that replicating the tagging is much more difficult and expensive for the criminal class than replicating the design!

But I digress. There are many older U.S. stamps showing representations of the flag, even though the earliest examples show the flag in monocolor. Let’s look at some of them.

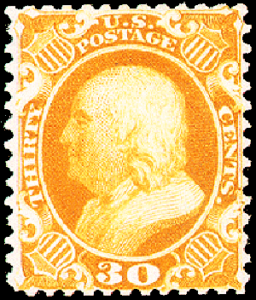

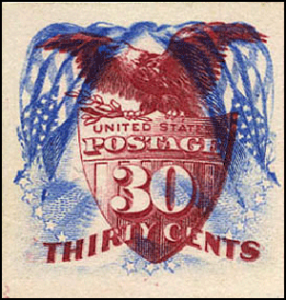

To the extent we think about it, most U.S. collectors would assume that the 30¢ 1869 stamp (Scott #121 at right) is the first issue with a U.S. flag. See the all-blue flags in the lower corners of the stamp? In fact, if one includes representations of the flag in the form of a shield, then the first U.S. stamp is the 30¢ Benjamin Franklin 1860 stamp (Scott #38). Note the stars-and-stripes shields in all four corners (below left). Had you ever noticed it before?

To the extent we think about it, most U.S. collectors would assume that the 30¢ 1869 stamp (Scott #121 at right) is the first issue with a U.S. flag. See the all-blue flags in the lower corners of the stamp? In fact, if one includes representations of the flag in the form of a shield, then the first U.S. stamp is the 30¢ Benjamin Franklin 1860 stamp (Scott #38). Note the stars-and-stripes shields in all four corners (below left). Had you ever noticed it before?

Would you like to guess how many face-different U.S. stamp designs include the various forms of the American flag? 25? 50? As many as 100? When I sat down with the catalogue to count them, I was surprised to tally over 200! Now, that does include denominated and non-denominated flag stamps that are otherwise the same, and the different color denominations of the 32¢ “G” definitives; but it does not include Stars-and-Stripes shields, or hard-to-identify dots flying from flag poles on federal buildings and ships, on monuments, uniforms, and airplanes.

Would you like to guess how many face-different U.S. stamp designs include the various forms of the American flag? 25? 50? As many as 100? When I sat down with the catalogue to count them, I was surprised to tally over 200! Now, that does include denominated and non-denominated flag stamps that are otherwise the same, and the different color denominations of the 32¢ “G” definitives; but it does not include Stars-and-Stripes shields, or hard-to-identify dots flying from flag poles on federal buildings and ships, on monuments, uniforms, and airplanes.

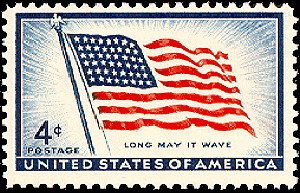

The first U.S. flag to be shown in color is the handsome 4¢ 1957 48-star flag (Scott #1094) shown on the right. The 1957 stamp also has the distinction of being the first U.S. stamp to be produced on the BEP’s new Giori press, which could do up to three colors from a single plate. Up to that point, multicolor stamps produced by BEP required separate plates for each color; a situation that required more time and effort, but also made the

The first U.S. flag to be shown in color is the handsome 4¢ 1957 48-star flag (Scott #1094) shown on the right. The 1957 stamp also has the distinction of being the first U.S. stamp to be produced on the BEP’s new Giori press, which could do up to three colors from a single plate. Up to that point, multicolor stamps produced by BEP required separate plates for each color; a situation that required more time and effort, but also made the  Bureau invert-prone. One of the inverts that resulted is on the 30¢ 1869, and you can see the upside down flags in the proof shown on the left (Scott #121aP4). One of the interesting aspects of U.S. stamp collecting is the search for what are called “design errors”; mistakes in the final design attributed to inadequate research, oversight, artistic license, and pure sloppiness.

Bureau invert-prone. One of the inverts that resulted is on the 30¢ 1869, and you can see the upside down flags in the proof shown on the left (Scott #121aP4). One of the interesting aspects of U.S. stamp collecting is the search for what are called “design errors”; mistakes in the final design attributed to inadequate research, oversight, artistic license, and pure sloppiness.

They are not valuable as every one of the stamps produced has the same error, but they do show that the public is watching, and they make take what might be an ordinary postage stamp and make it into a conversation piece. We’ll review a few of them, and a few that were questioned, to complete this column.

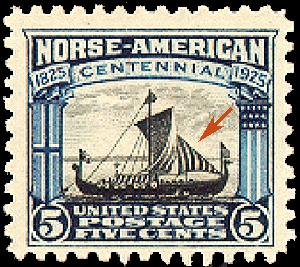

The 5¢ Norse-American stamp on the right (Scott #621) might be called a non-design error. It caused a bit of a sensation when it was issued in 1925 because the ship, clearly early Norse, not current American, is flying an American flag (arrow). The Post Office Department patiently explained that this was no mistake. The craft is a replica of a Viking “Dragon Ship”, and actually sailed from Norway to the United States between April 30, and June 13, 1893, to participate in the World’s Columbian Exposition. The stamp was designed using actual photographs of the replica.

The 5¢ Norse-American stamp on the right (Scott #621) might be called a non-design error. It caused a bit of a sensation when it was issued in 1925 because the ship, clearly early Norse, not current American, is flying an American flag (arrow). The Post Office Department patiently explained that this was no mistake. The craft is a replica of a Viking “Dragon Ship”, and actually sailed from Norway to the United States between April 30, and June 13, 1893, to participate in the World’s Columbian Exposition. The stamp was designed using actual photographs of the replica.

The 3¢ White Plains issue on the left was released in 1926 (Scott #629) for the 150th Anniversary of the Battle of White Plains, which took place on October 28, 1776. But the Stars and Stripes at the bottom left did not come into being until June 14, 1777.

The 3¢ White Plains issue on the left was released in 1926 (Scott #629) for the 150th Anniversary of the Battle of White Plains, which took place on October 28, 1776. But the Stars and Stripes at the bottom left did not come into being until June 14, 1777.

The 5¢ Flag over White House above raised a few eyebrows when it hit the streets. Note that it does not carry the words “United States” or the short form “U.S.”; one of only a few stamps to take that liberty. Nor does it contain the word “postage.” The latter is curious, but the former was likely deemed appropriate because the Flag design component marked this as an American issue in the same way that Queen Victoria’s presence on Great Britain #1 left no room for doubt as to its origin. The stamp did generate another question as there are only three red stripes next to the blue field of stars, while the correct number is four. Discussion resulted in a finding that the fourth stripe was present, but is hidden by the ripples of the flag.

the same way that Queen Victoria’s presence on Great Britain #1 left no room for doubt as to its origin. The stamp did generate another question as there are only three red stripes next to the blue field of stars, while the correct number is four. Discussion resulted in a finding that the fourth stripe was present, but is hidden by the ripples of the flag.

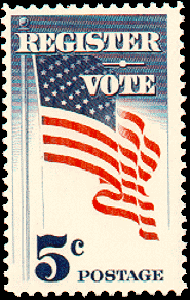

“Register & Vote” is a laudable message as portrayed on the 1964 5¢ commemorative stamp in Figure 8 (Scott #1249). But it is partially printed across the American Flag. This contravenes the Federal law governing use and presentation of the flag, which provides that nothing must be placed over it or on it when it is illustrated.

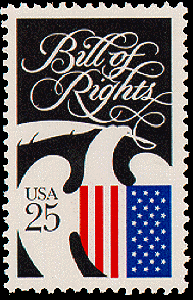

Another breach of etiquette is seen on the 25¢ “Bill of Rights” commemorative from 1989 (Scott #2421) seen in Figure 8. It should have been displayed with the stars on the left, and the stripes on the right; not as shown. A result is that we sometimes see the stamp applied upside down on covers as people observe correct flag —if not philatelic — etiquette.

Another breach of etiquette is seen on the 25¢ “Bill of Rights” commemorative from 1989 (Scott #2421) seen in Figure 8. It should have been displayed with the stars on the left, and the stripes on the right; not as shown. A result is that we sometimes see the stamp applied upside down on covers as people observe correct flag —if not philatelic — etiquette.

We have a case of an impossible design with regard to the flag on the 32¢ Flag Over Porch stamp in Figure 9 (Scott Design Type A2212). This is complicated, so I will quote from “Flag Faux Pas;” a short article in the July, 1996, Scott Stamp Monthly:

“Those who know the flag well will immediately see something amiss, but identifying the problem is slightly harder. The U.S. flag has 13 stripes, seven of which do not span the entire width of the flag, because of the field.

“Those who know the flag well will immediately see something amiss, but identifying the problem is slightly harder. The U.S. flag has 13 stripes, seven of which do not span the entire width of the flag, because of the field.

“The field contains 50 stars in nine rows (five rows of six and four rows of five). Because there are only seven incomplete stripes, all nine rows must feature stars shorter than any stripe. Those on the stamp are larger. It would therefore be an impossibility to fit all 50 stars in this flag’s field.”

There are many other stamps and many other stories that go with them, but we have only so much space here. For the flag connoisseur there are also cancellations with flags in them, cachets with flags part of the design, covers in the form of flags, and a wide variety of Errors, Freaks and Oddities on U.S. Flag stamps.

And if that is not enough to keep you busy, you can branch out into military and State Flags on U.S. stamps, Confederate Flags (dare I say), and even foreign flags on U.S. stamps. The Flag subject is a gift that keeps on giving! (Show at left: The 2017 U.S. Flag stamp.)

And if that is not enough to keep you busy, you can branch out into military and State Flags on U.S. stamps, Confederate Flags (dare I say), and even foreign flags on U.S. stamps. The Flag subject is a gift that keeps on giving! (Show at left: The 2017 U.S. Flag stamp.)

Should you wish to comment on this column, or have questions or ideas you would like to have explored in a future column, please write to John Hotchner, VSC Contributor, P.O. Box 1125, Falls Church, VA 22041-0125, or email, putting “VSC” in the subject line.

Or comment right here.

John-I Have 10 +lbs of “F”stamps+ M&U-I am 78 with Alzheimwer’s-I am very slow,how can I collect them with no catalog as aguideline.Except the F/Porch stamp .32 catalog which I have. There are so many varities with so many stamps issued,how will I know when my list is complete. Is there such a stamp club.Pls advise as best you can-appreciate it very very much. Thank you!!

Bill Stahl,Springfield, Or.

I have and am happy to provide a list of the different F and 29c tulip varieties. Contact me at jmhstamp@verizon.net and I will send you a copy. John