[press release]

Royal Mail Issues New Leonardo da Vinci Special Stamps

- 12-stamp set features some of Leonardo da Vinci’s most beautiful and intriguing works

- 2019 marks 500 years since Leonardo’s death

- The images featured on the Leonardo da Vinci stamps were chosen to coincide with the 12 exhibitions, ‘Leonardo da Vinci: A Life in Drawing’, taking place across the UK this year

- The images are from the Royal Collection, which holds the most important collection of drawings by Leonardo da Vinci due to the breadth of topics represented. They are housed in the Print Room at Windsor Castle

- Included is a stamp featuring a drawing of St Philip, a preparatory work for Leonardo’s masterpiece, The Last Supper

- Some of the stamps feature Leonardo’s reverse ‘mirror writing’

- The stamps are available at www.royalmail.com/leonardo

Royal Mail is issuing Leonardo da Vinci stamps on Wednesday 13 February.

Leonardo is widely considered one of the greatest artists of all time, and 500 years since his death his drawings, in which he explored fields as diverse as botany, anatomy, portraiture, design and the nature of the world around him, continue to fascinate.

The drawings featured on the stamps were chosen to coincide with the 12 exhibitions, ‘Leonardo da Vinci: A Life in Drawing’, taking place in 2019 across the UK – one drawing from each of the 12 exhibitions is featured on a stamp.

Leonardo da Vinci was one of history’s greatest polymaths – a painter, sculptor, architect, engineer and map-maker who also pursued the scientific study of subjects as diverse as human anatomy, the theory of light, the movement of water and the growth of plants.

The common thread to all Leonardo’s work was drawing. He drew incessantly, for new ideas, to refine compositions, to record his observations and to test his theories. Many of his drawings are accompanied by extensive notes in ‘mirror-writing’: Leonardo was left-handed, and throughout his life he habitually wrote in perfect mirror image, from right to left.

Fewer than 20 paintings by Leonardo survive, and nothing in sculpture or architecture. But because Leonardo hoarded thousands of his drawings and dozens of notebooks, many of which have been passed down through succeeding centuries, we have a detailed knowledge of the workings of his extraordinary mind.

The Royal Collection holds the greatest collection of Leonardo’s drawings in existence, housed in the Print Room at Windsor Castle. Because they have been protected from light, fire and flood, they are in almost pristine condition and allow us to see exactly what Leonardo intended – and to observe his hand and mind at work, after a span of five centuries. These drawings are among the greatest artistic treasures of the United Kingdom.

Martin Clayton, Head of Prints and Drawings, Royal Collection Trust, said: ‘Alongside an ambitious programme of 12 exhibitions around the UK, then exhibitions at The Queen’s Galleries in London and Edinburgh, we are thrilled to be working with Royal Mail on this special 12-stamp set, which invites everyone to join the celebration of Leonardo and his work in 2019.’

Philip Parker, Royal Mail, said: “500 years after his death, Leonardo’s drawings continue to inspire and intrigue us. We are delighted to feature 12 of the finest examples from the Royal Collection on these stamps.”

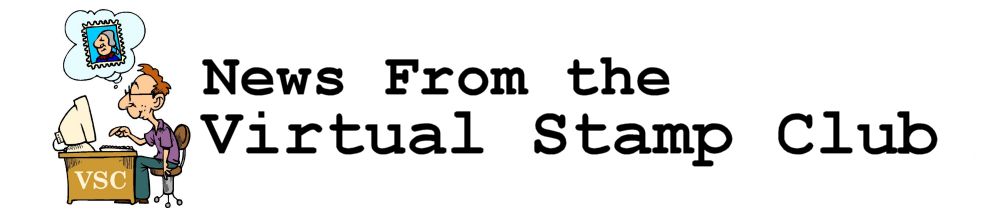

Pen and ink

Ulster Museum, Belfast

Leonardo had little access to human material when he first started to study anatomy. But in 1489, he obtained a skull, which he cut in a variety of sections to study its structure. In this drawing, he shows the skull sawn down the middle, then across the front of the right side. This beautifully lucid presentation, with the two halves juxtaposed, allows the viewer to locate the facial cavities in relation to the surface features. Leonardo wished to determine the proportions of the skull and the paths of the sensory nerves, believing that they must converge at the site of the soul.

Leonardo had little access to human material when he first started to study anatomy. But in 1489, he obtained a skull, which he cut in a variety of sections to study its structure. In this drawing, he shows the skull sawn down the middle, then across the front of the right side. This beautifully lucid presentation, with the two halves juxtaposed, allows the viewer to locate the facial cavities in relation to the surface features. Leonardo wished to determine the proportions of the skull and the paths of the sensory nerves, believing that they must converge at the site of the soul.

A Sprig Of Guelder-Rose, c.1506–12

Red chalk on orange-red prepared paper

Sunderland Museum and Winter Gardens

A beautifully rendered study of guelder-rose (Viburnum opulus) has been drawn in red chalk on paper rubbed all over with powdered red chalk. Although it may be connected with Leonardo’s Leda and the Swan, it is far more detailed than necessary as a study for a painting; indeed, it surpasses anything found in contemporary herbals. The leaves are shown curling and sagging, for Leonardo was interested not merely in their shape but also in their living form when subject to the natural forces of growth and gravity.

A beautifully rendered study of guelder-rose (Viburnum opulus) has been drawn in red chalk on paper rubbed all over with powdered red chalk. Although it may be connected with Leonardo’s Leda and the Swan, it is far more detailed than necessary as a study for a painting; indeed, it surpasses anything found in contemporary herbals. The leaves are shown curling and sagging, for Leonardo was interested not merely in their shape but also in their living form when subject to the natural forces of growth and gravity.

Studies Of Cats, c.1517–18

Pen and ink

Bristol Museum and Art Gallery

Leonardo’s studies of sleeping cats are among his most sensitively observed drawings and must have been done directly from life. His appreciation of the animals’ lithe forms had a scientific basis, for elsewhere on the sheet he wrote: “Of flexion and extension. The lion is the prince of this animal species, because of the flexibility of its spine.” This suggests that the drawings were made in connection with Leonardo’s proposed treatise on “the movements of animals with four feet, among which is man, who likewise in his infancy crawls on all fours”.

Leonardo’s studies of sleeping cats are among his most sensitively observed drawings and must have been done directly from life. His appreciation of the animals’ lithe forms had a scientific basis, for elsewhere on the sheet he wrote: “Of flexion and extension. The lion is the prince of this animal species, because of the flexibility of its spine.” This suggests that the drawings were made in connection with Leonardo’s proposed treatise on “the movements of animals with four feet, among which is man, who likewise in his infancy crawls on all fours”.

A Star-Of-Bethlehem And Other Plants, c.1506–12

Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum

Glasgow

Leonardo drew plants and flowers as studies for decorative details in his paintings and probably also in the process of working towards a systematic treatise on the growth of plants and trees. His finest botanical drawings were executed for his painting Leda and the Swan, which was to have a foreground teeming with plants and flowers, thus echoing the fertility inherent in that myth. The focus of this drawing is a clump of star-of-Bethlehem (Ornithogalum umbellatum), whose swirling leaves are seen in studies for, and copies of, the lost painting.

Leonardo drew plants and flowers as studies for decorative details in his paintings and probably also in the process of working towards a systematic treatise on the growth of plants and trees. His finest botanical drawings were executed for his painting Leda and the Swan, which was to have a foreground teeming with plants and flowers, thus echoing the fertility inherent in that myth. The focus of this drawing is a clump of star-of-Bethlehem (Ornithogalum umbellatum), whose swirling leaves are seen in studies for, and copies of, the lost painting.

The Anatomy Of The Shoulder And Foot, C.1510–11

Pen and ink with wash

Southampton City Art Gallery

Leonardo was fascinated by the mechanism of the shoulder and by how the arrangement of muscles and bones allowed such a wide range of movement. Here he analyses the shoulder and arm in a series of drawings at progressive states of dissection. He begins at upper right with the muscles intact and then lifts away individual muscles, such as the deltoid and biceps, to reveal the structures below. At lower right, Leonardo demonstrates the articulation of the ankle with the tibia and fibula lifted away from the foot.

Leonardo was fascinated by the mechanism of the shoulder and by how the arrangement of muscles and bones allowed such a wide range of movement. Here he analyses the shoulder and arm in a series of drawings at progressive states of dissection. He begins at upper right with the muscles intact and then lifts away individual muscles, such as the deltoid and biceps, to reveal the structures below. At lower right, Leonardo demonstrates the articulation of the ankle with the tibia and fibula lifted away from the foot.

The Head Of Leda, C.1505–08

Pen and ink over black chalk

Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool

Over the last 15 years of his life, Leonardo worked on a painting of the myth of Leda, showing the queen of Sparta seduced by the god Jupiter in the guise of a swan. The painting was the highest valued item in Leonardo’s estate at his death; it later entered the French royal collection but was apparently destroyed around 1700. In this sketch, Leonardo expended little effort on Leda’s demure downward glance, devoting his attention instead to the most complicated of hairstyles – throughout his life he had a love of personal adornment in both hair and clothes.

Over the last 15 years of his life, Leonardo worked on a painting of the myth of Leda, showing the queen of Sparta seduced by the god Jupiter in the guise of a swan. The painting was the highest valued item in Leonardo’s estate at his death; it later entered the French royal collection but was apparently destroyed around 1700. In this sketch, Leonardo expended little effort on Leda’s demure downward glance, devoting his attention instead to the most complicated of hairstyles – throughout his life he had a love of personal adornment in both hair and clothes.

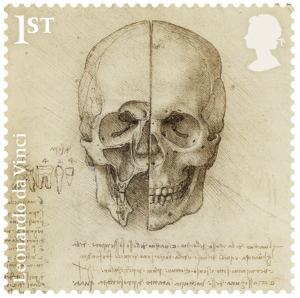

The Head Of A Bearded Man, C.1517–18

Black chalk

Derby Museum and Art Gallery

Leonardo was fascinated by the male profile, both the divinely beautiful and the hideously grotesque. Such heads are found throughout his work, from paintings such as The Last Supper to quick doodles in the margins of his drawings. Towards the end of his life, Leonardo made many carefully finished drawings of classical profiles, exercises in form and draughtsmanship simply for his own satisfaction. Their features – such as the dense mat of curly hair seen here – were inspired by ancient coins and medals of Roman emperors.

Leonardo was fascinated by the male profile, both the divinely beautiful and the hideously grotesque. Such heads are found throughout his work, from paintings such as The Last Supper to quick doodles in the margins of his drawings. Towards the end of his life, Leonardo made many carefully finished drawings of classical profiles, exercises in form and draughtsmanship simply for his own satisfaction. Their features – such as the dense mat of curly hair seen here – were inspired by ancient coins and medals of Roman emperors.

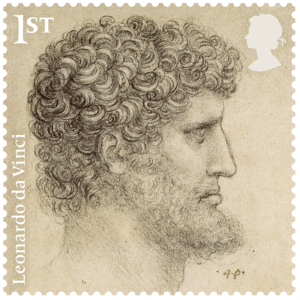

The Skeleton, C.1510–11

Pen and ink with wash

Amgueddfa Cymru/National Museum Wales, Cardiff

Leonardo’s most brilliant anatomical studies were conducted in the winter of 1510–11, when he was apparently working in the medical school of the university of Pavia, near Milan. He may have dissected up to 20 human bodies at that time, concentrating on the mechanisms of the bones and muscles. This is his most complete representation of a skeleton, seen from front, side and back in the manner of an architectural drawing. Leonardo aimed to compile an illustrated treatise on human anatomy, but his studies remained unpublished at his death.

Leonardo’s most brilliant anatomical studies were conducted in the winter of 1510–11, when he was apparently working in the medical school of the university of Pavia, near Milan. He may have dissected up to 20 human bodies at that time, concentrating on the mechanisms of the bones and muscles. This is his most complete representation of a skeleton, seen from front, side and back in the manner of an architectural drawing. Leonardo aimed to compile an illustrated treatise on human anatomy, but his studies remained unpublished at his death.

The Head Of St Philip, C.1495

Black chalk

Millennium Gallery, Sheffield

Leonardo’s greatest completed work was The Last Supper, painted in the refectory of the monastic church of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan and now in a ruined state. The mural shows the reaction of the disciples to Christ’s announcement of his imminent betrayal. Few drawings survive of the hundreds that must have been made. This study for the head of St Philip, leaning towards Christ in devotion and despair, was probably based on a live model, but Leonardo has idealised the features, taking them out of the real world and into the divine.

Leonardo’s greatest completed work was The Last Supper, painted in the refectory of the monastic church of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan and now in a ruined state. The mural shows the reaction of the disciples to Christ’s announcement of his imminent betrayal. Few drawings survive of the hundreds that must have been made. This study for the head of St Philip, leaning towards Christ in devotion and despair, was probably based on a live model, but Leonardo has idealised the features, taking them out of the real world and into the divine.

A Woman In A Landscape, C.1517–18

Black chalk

Manchester Art Gallery

Two of Leonardo’s favourite devices – a mysterious smile and a pointing hand – are combined in this ethereal drawing. It shows a woman standing in a rocky, watery landscape, smiling at us while gesturing into the distance, her arms gathering her drapery to her breast. The most plausible explanation is that this is the maiden Matelda gathering flowers, as she appears to Dante on the far side of a stream in Purgatory, the second book of his Divine Comedy. However, the purpose of the drawing is unknown.

Two of Leonardo’s favourite devices – a mysterious smile and a pointing hand – are combined in this ethereal drawing. It shows a woman standing in a rocky, watery landscape, smiling at us while gesturing into the distance, her arms gathering her drapery to her breast. The most plausible explanation is that this is the maiden Matelda gathering flowers, as she appears to Dante on the far side of a stream in Purgatory, the second book of his Divine Comedy. However, the purpose of the drawing is unknown.

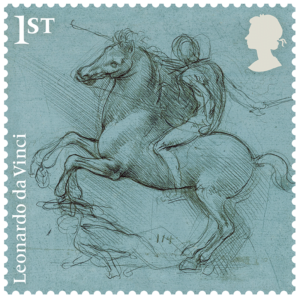

A Design For An Equestrian Monument, C.1485–88

Silverpoint on blue prepared paper

Leeds Art Gallery

Ludovico Sforza, ruler of Milan, commissioned Leonardo to execute a bronze equestrian monument, well over life size, to his father, Francesco. Leonardo’s early studies show Francesco on a rearing horse over a fallen foe. Over the next five years, Leonardo built a full-sized clay model of the horse and prepared a mould for the casting – a huge technical challenge. But in 1494, Ludovico requisitioned the 75 tonnes of bronze for the cast to make cannon, and the monument was never finished. Invading French troops used the clay model for target practice, destroying it.

Ludovico Sforza, ruler of Milan, commissioned Leonardo to execute a bronze equestrian monument, well over life size, to his father, Francesco. Leonardo’s early studies show Francesco on a rearing horse over a fallen foe. Over the next five years, Leonardo built a full-sized clay model of the horse and prepared a mould for the casting – a huge technical challenge. But in 1494, Ludovico requisitioned the 75 tonnes of bronze for the cast to make cannon, and the monument was never finished. Invading French troops used the clay model for target practice, destroying it.

The Fall Of Light On A Face, C.1488

Pen and ink

Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery

During the 1480s, Leonardo began to assemble material towards a treatise on the theory of painting. His own paintings, such as the Mona Lisa, were noted even in his own day for their sophisticated treatment of shadows, and here he sets out the geometrical principles of light and shade. The diagram and notes (in mirror writing) explain that where the light falls at right angles on the face, the face will be most strongly illuminated; where it falls at a shallow angle, the face will be less strongly lit; and where no light is received, under the nose and chin, the surface will be completely dark.

During the 1480s, Leonardo began to assemble material towards a treatise on the theory of painting. His own paintings, such as the Mona Lisa, were noted even in his own day for their sophisticated treatment of shadows, and here he sets out the geometrical principles of light and shade. The diagram and notes (in mirror writing) explain that where the light falls at right angles on the face, the face will be most strongly illuminated; where it falls at a shallow angle, the face will be less strongly lit; and where no light is received, under the nose and chin, the surface will be completely dark.

About The Royal Collection

Royal Collection Trust, a department of the Royal Household, is responsible for the care of the Royal Collection and manages the public opening of the official residences of The Queen. Income generated from admissions and from associated commercial activities contributes directly to The Royal Collection Trust, a registered charity. The aims of The Trust are the care and conservation of the Royal Collection, and the promotion of access and enjoyment through exhibitions, publications, loans and educational programmes. Royal Collection Trust’s work is undertaken without public funding of any kind.

The Royal Collection is among the largest and most important art collections in the world, and one of the last great European royal collections to remain intact. It comprises almost all aspects of the fine and decorative arts, and is spread among some 15 royal residences and former residences across the UK, most of which are regularly open to the public. The Royal Collection is held in trust by the Sovereign for her successors and the nation, and is not owned by The Queen as a private individual.

The Royal Collection contains by far the greatest collection of drawings by Leonardo da Vinci. The group of more than 550 sheets has remained together since Leonardo’s death in 1519. Because of the potential for damage from exposure to light, these very delicate works on paper can never be on permanent display and are kept in carefully controlled conditions in the Print Room at Windsor Castle. All the drawings can be viewed online on the Royal Collection Trust website at www.rct.uk/collection.

Exhibition dates:

Leonardo da Vinci: A Life in Drawing (1 February – 6 May 2019)

Exhibitions at 12 UK venues

Leonardo da Vinci: A Life in Drawing (24 May – 13 October 2019)

Exhibition of over 200 drawings

The Queen’s Gallery, Buckingham Palace, London

Leonardo da Vinci: A Life in Drawing (22 November 2019 – 15 March 2020)

Exhibition of 80 drawings

The Queen’s Gallery, Palace of Holyroodhouse, Edinburgh